Definition: Myrmecologist—noun, 1. An entomologist who makes a special study of ants, or of myrmecology. 2. One who studies ants.

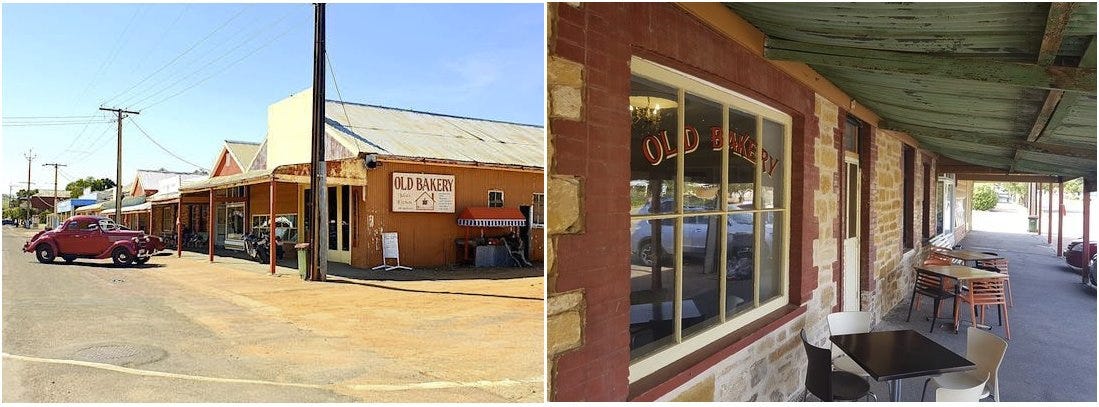

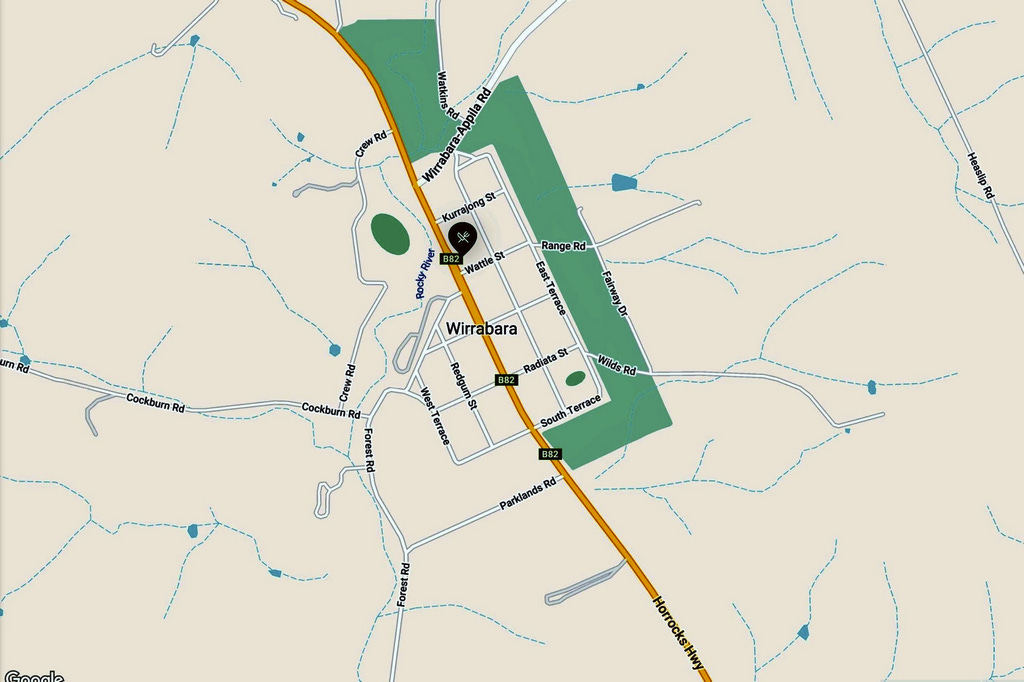

The field trip after the Australian Social Insect Congress is underway, two minivans packed with myrmecologists. Wirrabarra is just a wide spot in the road between Adelaide and the Flinders Ranges, a straggle of agriculture-oriented businesses selling Kohatsu tractors, fertilizer and seed, interspersed with modest offerings for the tourist enroute to or from the Flinders Ranges. It lies just far enough from the mountains that a spot of tea has general appeal.

The hand-lettered chalkboard in front of Anna’s Tea Shop offers not only tea but also meat pies, veggie pies, kangaroo pies and sausage rolls. Just what a bunch of sleepy, bored and hungry myrmecologists need. The two minibuses pull up to the curb and 21 myrmecologists straggle out, stretching and yawning. Masaki staggers out last, looking dazed, the towel still tied around his head, samurai-style. Jürgen immediately strolls up to one of the porch-posts and inspects it from a distance of a few inches, as though communing with the post, his cricket hat pushed back on his head by the post. Andreas engages a flower box in intimate conversation. An old man sits in a chair on the front porch of the tea shop, his leg propped on a box and a crutch leaning against the porch rail. He peers at the sudden crowd through his thick glasses, his mouth open. It is hot and his limp, white shirt sticks to his chest. His face suggests it has been a long, customer-free morning.

Inside the tea shop, a look of anxiety settles on the proprietress’ face as the door opens time and again to fill the small room with customers. She is alone. Soon however, her face takes on a look of determination as she mentally girds her loins to deal with this sudden flood of customers. One by one, we order. Jürgen points to a meat pie in the case. What is that? Meat pie. I’ll take it, he says. Riita shudders. That’s disgusting, she says. She orders a spinach pie, but not before she has delivered, free of charge, a mini-lecture on the repulsiveness of eating meat. Andreas and Fabrizio hover indecisively over the display case. Terry hovers solicitously over Amelia. What do you feel like eating? Finally, all orders are complete. Meat pie, kangaroo pie, spinach pie, sausage roll, Fanta, beer and ice cream on a stick. Find a seat, I’ll bring it to you, she repeats to each of us.

The building is old, perhaps 1880. Plaster over thick sandstone form the interior walls, and there are lace tablecloths on the tables. An old-fashioned tea room look. Andreas gets his food first. He immediately scatters a few flakes of pastry and some jam on the windowsill, baiting for ants. Within minutes, they arrive. His vial and forceps lie at ready while he eats. Terry wanders in, still hovering over Amelia. All seats are taken, so they wander into the adjacent room. Masaki is already asleep at the table against the wall, his chin on his chest, snoring sonorously.

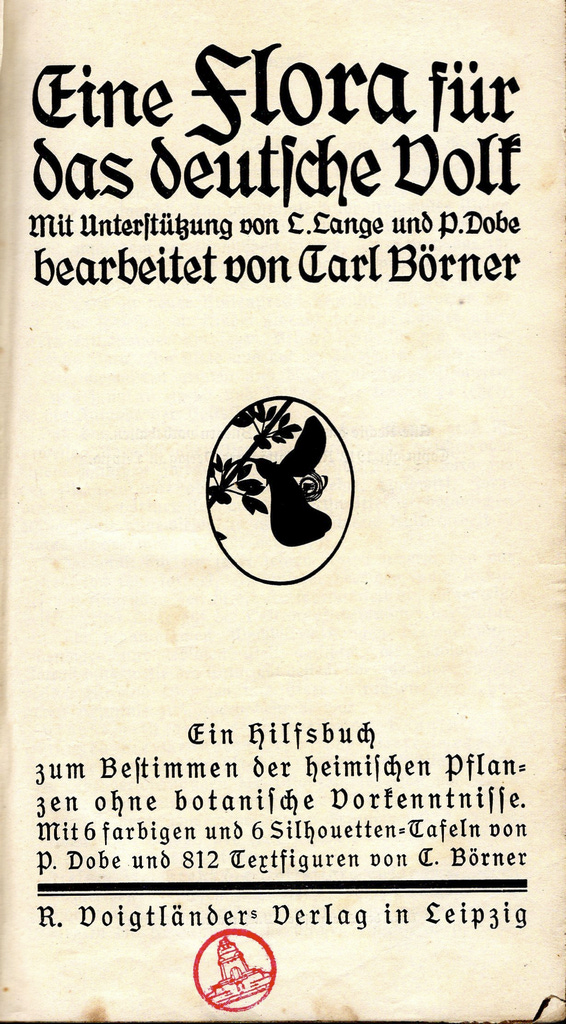

A couple of small German books in gothic type with titles such as “Schwach Doch Stark” (weak yet strong) lie on the lace tablecloth, moral tales for young people. Inside one is a hand-colored postcard from Jerusalem, the Mount of Olives in the background, the Temple on the Rock in the foreground. An inscription identifies the book as having belonged to Arthur Keller, who purchased it in 1907.

I push the books across to Karil. Can you read this? I say. He flips open the cover and leafs through a few pages. I taught myself German script when I was a student, he answers.

Script? Or type? I ask. Nobody hand-writes the print form (aka Fraktur).

The script. Handwriting, he says.

This is beginning to take on mysterious dimensions. As far as I know, Finns have no use for German script. For that matter, neither do Germans anymore. Its use was in steep decline even before World War II. My grandfather used it, and handwrote a book of my grandmother’s recipes. My mother learned and could read it but did not use it. I once learned to read it but have forgotten how. So, Karil, the Finn, went out of his way to learn what even then was a vanishing form, one never used in his native Finland.

A benighted look must have clouded my face, for Karil began, with considerable enthusiasm, to explain. When I was a student, I kept detailed field notes of the bird species I saw and where I saw them. I used German script so people couldn’t read my notes and steal my observations. I had a lot of details.

Words failed me, but there was more.

Yes, I kept all my notes in German script. I had a special system for abbreviating the species names too, so that even if someone could read the script, they wouldn’t be able to tell what species it was about. I never used the obvious abbreviation. For common birds I might use an abbreviation of a word that meant the same thing as the generic name, but in English, then add the first three letters of the specific name.

Yes, I said, one can’t be too careful.

In the spirit of Karil, I considered writing this essay in German script (which I can’t do) so nobody could read it, or in Fraktur, which is possible, I suppose, but why would I do either? Unlike Karil, I have no sightings of birds I want to keep secret. On the other hand, I do have multiple sightings of a variety of myrmecologists, but they do not yet qualify for species status. Perhaps someday they will.

Strange birds, these myrmecologists. Happy you captured a sample of their curious behaviors.

You are wonderfully descriptive and creative, crafting fascinating essays on a variety of subjects, always delightful. Thanks so much.