Shortly after we got married in 1968, I built a dining table on the floor of (where else?) our dining room. It kept the dishes off the floor for 28 years and I hardly noticed that it was gradually showing the wear and tear that comes with a long life. My wife, Vicki noticed, however. A new dining room table got added to the list of woodworking wishes she keeps in her head, and in pretty short order, it got moved to the top of the list. “That old table is no longer of a quality suitable for our house”, she sniffed. “It’s a piece of grad student junk”. I had to agree that it had lost some its youthful elegance, so I started planning a new table. Actually, it wasn’t so much that I planned it, as that it evolved gradually out of a long series of Adventures in Woodworking.

Like a lot of guys, I enjoy scrounging, and scrounging wood tops the list. “A boy”, I will intone at the appropriate moment, “can’t have too much lumber.” Or get it too cheap, I might have added. And so my garage workshop soon acquired a lean-to lumber shed, which doubled in size when we moved to a new house in 1989. It was filled with lumber from two primary sources. Salvaged heart pine from several turn-of-the-century (19th to 20th) buildings, mostly acquired free or dirt-cheap, and a bunch of cherry rescued from the cerambicid beetles.

Here in north Florida, a lot of people who own forested land think hardwoods are junk trees and steal vitality from pines, so they inject these hardwoods with herbicide to kill them, and then leave them to the insects and fungi to fell. To a scrounge like me, this is an open invitation. So about 15 years ago, I got two friends, a pickup truck and a “thick-back” crosscut saw salvaged from a barn back when we lived in Ithaca, and we cut down two substantial cherry trees that had recently transpired their last, after a dose of herbicide.

By word of mouth, I had heard of a country-boy down in Wakulla County, south of Tallahassee, who had a sawmill and did custom work. As he had no phone, we simply showed up with the logs in the bed of the pickup. Buddy turned out not to be the tobacco-chewing old redneck I had expected, but a young guy who was a bigger scrounge than anyone I knew. The reason he had bought the sawmill, he told us, was because he wanted to build himself a house, and for a house, one needed lumber, and to get lumber, one needed a means of sawing up trees, of which there were plenty around.

The sawmill was old, but recently purchased. A 50-inch circular blade was powered by a 1938 Allis-Chalmers gasoline engine whose radiator had to be refilled every 20 minutes or so. The log carriage was pulled by a steel cable, and the whole outfit had a respectable coating of rust (in Florida, if it’s got ahrn (iron), it’s got rust). My friends and I caught the boards as they came off the saw, and pretty soon, we were heading home with a sizable haul of mighty pretty cherry. This stock was turned into several pieces of furniture, as well as trim for a re-laid maple floor that I scrounged from an old tobacco warehouse (but that’s another story). Some of it eventually also ended up in the new dining room table.

But there’s another thread to weave into this story, and it involves a tree surgeon and another cherry tree. By this time, the beauty of the wood in cherry crotches had grabbed my attention, so I called several tree services and asked them to let me know if they got a large cherry fork. Imagine my surprise when one of them actually called me several weeks later. Having experimented with smaller forks, I knew this 2 foot diameter, 5 foot-long monster would have to dry as a block for quite a while. To modify slightly the motto found at the bottom of menus in greasy-spoon restaurants, “Good wood takes time to prepare”. So, with a borrowed chain saw, I blocked out the heart that contained the fancy patterns and let this 10” x12” x 5’ chunk dry for, what?, four or five years. Finally, I cut it in half, longitudinally, and found the flame-pattern to be every bit as beautiful as I had hoped it would be.

A couple of years later, I borrowed the use of a large band saw capable of sawing wood up to ten inches thick. It came off a Navy destroyer after WWII, and sported the name, DOALL. You won’t be impressed with my brainpower if I admit that for several years, I thought that maybe the guy who started the company that made the band saw had been named DOALL, and that his name rhymed with mole. Anyway, with this great, gray hulk and a six-teeth-per-inch blade tightened to a middle-C note, I managed to convert the large block into a whole stack of 1/8” veneers, each with the rippling frozen flames traversing its diagonal. As every true wood-scrounge knows, converting log into board is a mighty satisfying experience, and I bathed in satisfaction for a long time. Mind, I still had no idea of what I was going to build with these veneers, nor was I to get an idea for several more years.

This is where we get back to the original theme. When my wife said, “Don’t you think it’s time for a new dining room table?”, I knew that it would somehow incorporate the veneers and the purloined cherry. I also knew that the pretty veneer wasn’t going to be on the underside of the table. So that part was easy. I got a 4’ x 8’ sheet of birch plywood, and set out to glue the veneers onto it.

Now came the problem of thicknessing these not-so-uniform veneers so the tabletop wouldn’t have that homey rippled look after the veneers were glued down on it. A tentative run of an expendable piece of veneer through my Ryobi portable planer left me with quite a little pile of chips and chunks, and without any doubt that this was not the method of choice for thicknessing. Finally, I located another country guy living way out on dirt roads amongst the gators and stray hound-dogs, who had a thickness sander, and who helped me out.

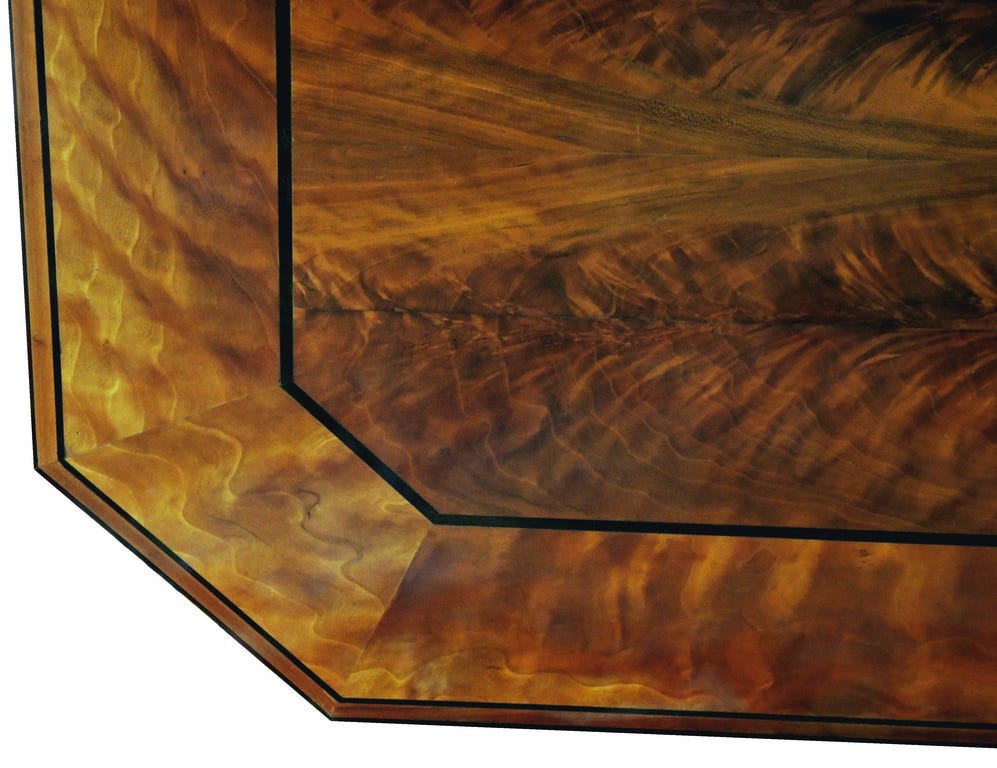

Even though the veneers were now even thickness, they weren’t really flat because the wood on opposite sides of the center experienced different shrinkage, and warped the veneers slightly. Too much to risk gluing as they were. The solution was to saw each veneer down its center, relieving the strain, then straightening all the edges and preparing them for gluing. This meant deciding on a pattern. A couple of months of dithering over the pattern, and I finally chose a book-matched and mirrored layout, reasoning that this wood was so beautiful, it didn’t need any fancy layout.

Fine Woodworking magazine is full of advice on how to veneer using a vacuum press and stuff like that. My shop, however, was entirely vacuum-free. How to clamp or pressure the veneers against the plywood during gluing? Ordinary weights were insufficient for such thick veneers, and the plywood too wide for most of its surface to be reachable by clamps. Garages, of course, weigh quite a lot, so finally, I devised a method by which I laid the plywood on the floor, glued one row of veneer, placed a layer of wax paper and a 2x10 over the row, and then wedged several upright 2 x 10’s between the one on the floor and the garage rafters. By hammering these boards into nearly vertical positions, I could bring the whole weight of the garage to bear on the veneers below. Of course, occasionally I hammered one in enough to raise the rafter and release the previous 2x10, which then fell on my head. It took five sessions to glue all the veneers, and then seven more to counter-veneer the underside. So now I had a tabletop, nicely veneered and counter-veneered but still no idea of what I was going to use to keep it off the floor.

I have always liked furniture with an architectural flavor, and Vicki and I finally hit on the right look--- big, thick legs that tapered toward the top, the fat end on the floor. Now all that purloined cherry was dusted off, a few powder-post beetles were evicted and I went to work. My wife raised the ante by suggesting that, “you might as well make it an extension table”, so a five-foot long extension slide was added to the table and the top was sawn into three pieces, the middle one being a two-foot removable leaf. This dissection took place on the garage floor using a Skill saw and a straightedge, followed by a careful trim of the edges with a router. In making the extension slide from a couple of beautiful pieces of heart pine that took about 70 years to grow 4 inches, I discovered that the fit isn’t too critical for such a long slide. Some candle wax rubbed on the slides made them move “real good.” I kept my fingers crossed that my wife wouldn’t come up with anymore sentences that started with, “You might as well…”

Of course, the table had to have my signature ebony trim strips. That went without saying, but I was running low on ebony. An ad in Fine Woodworking and a phone call to Tim in Portland soon had 50 Gabon ebony guitar frets winging in my direction. The pattern on the tabletop was built from the central veneered area outward, gluing on strips of ebony, alternating with a wavy-grain cherry veneer that I had produced from some pieces rescued from the sawmill’s burn pile. Then some ebony inlays and trim on the legs and the frame, and the base was ready to assemble. Because the legs were hollow, the joints between the legs and the frame got kind of complicated, so complicated I am not sure I remember how I did it. Maybe you can figure it out from the image below.

But eventually, it was all together, the top attached to the frame. It looked like a real table but the top surface needed leveling, what with the perimeter veneers not all being the same thickness as the central ones. This meant many hours with a straight-edge, a belt sander and a scraper. In the Florida heat, this also meant keeping a brow-wiping towel in my back pocket so I wouldn’t get sweat stains on my freshly sanded surface.

But now the story gets kind of boring. Everybody who reads Fine Woodworking magazine knows what you do after you get the whole thing assembled. Sanding, scraping, more sanding, more scraping, and finally finishing. This cherry was full-blooded, not that anemic, fast-grown stuff, so no staining was necessary to achieve a rich tone. A lot of woodworkers favor some really gorgeous but labor intensive finishes using hints of beeswax from wild bees nesting in hollow Carpathian oaks, shellac from Javan lac insects harvested under a full moon, Chinese tung oil, and Baltic linseed oil to make a finish that will water-stain at first opportunity. However, because this was a dining table, and we fully intended to dine upon it, complete with spilled wine, thumping glasses, dragged serving dishes and all, while between meals, there would be cats napping, Barbie dolls romping, homework and newspapers, we therefore opted for an indestructible polyurethane finish that made the beautiful grain shine as with an internal light. My garage shop was far too dusty, so we lugged the table into the living room, and endured the fumes through three thinned coats of polyurethane, applied with a brush and a furrowed brow.

The finished table looks like it was made for our decor, which, come to think of it, it was. My wife, my daughter, our cats, the Barbies, and our guests all love it. It was worth the 12 years it took to bring to life. But if I had to make a living building tables like this, I’d have been dead 11 years ago.

An addendum: As our daughter watched me build the new dining table, she asked if I would build her one too. Sure, I said. So here it is—-

Of course, she wanted it for her dolls, so here she is for scale.

Love the story - love the table(s). Hi Dennis! Such remarkable talent and craftsmanship!

Walter,

Oh my goodness what a treat thank you for sharing your personal stories and insights and while I find it fascinating I think it might be inspiring actually for Regine as she is created so much with so little so often. I'm still trying to inspire her to build musical instruments which she's not yet moved to do but perhaps another day... We actually attended a class in North Carolina John C. Campbell school where they build a banjo from native materials (regine actually attended earlier class where she went into the woods and helped out a bunch of small trees and created a delightful large chair and stool for me to sit in and play music that resides currently in our home in North Carolina). and then the Director suggested we can teach you how to play the next week and if you don't like to play the Banjo we will teach you how to make a potted plant out of the Banjo itself. We would like to invite you guys to dinner now it's the new year has clicked into 2024 and for at least 24 hours we're back from Cuba (came back last night at 9 o'clock) so let us know your availability over the next several weeks... Tim