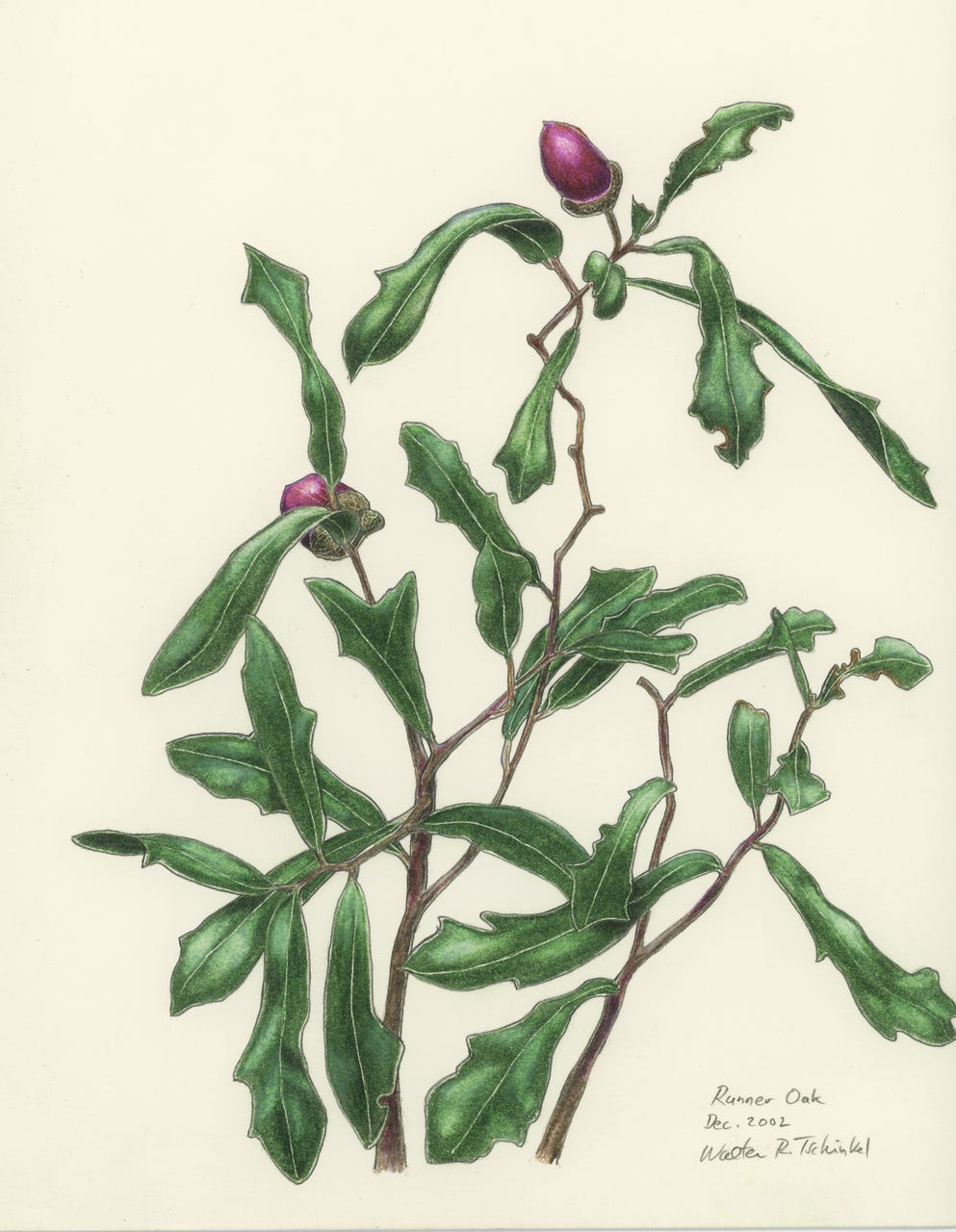

A walk in the higher, drier areas of the piney flat woods of Florida often takes you through dense, ankle-high ground cover of a tough-leaved woody plant that, on closer inspection, bears acorns, in other words, is an oak. Now, most people would expect oaks to be trees, and would be surprised by the identity of this scruffy, creeping stuff. No mighty oak, this! Or is it?

Pulling up some of the plants reveals more surprises, for all the plants in a patch, even when the patch is large, are connected by underground stems that sprout branches, roots and leafy, above-ground shoots at intervals. The entire connected patch is probably a single individual, an oak clone. So, what we have here is a tree that has gone underground, a lazy tree that saw no advantage in putting a lot of expensive resources into a weighty trunk to create a lofty, shady canopy, and seems satisfied with shooting up short, dinky branches while lying down.

On closer examination, it begins to look less like laziness and more like good sense. Runner oaks (there are two species in the flatwoods) grow in a habitat that, under natural conditions, burned every two or three years, so it would be rare indeed for the tree to grow tall enough to avoid death in the next fire. So rather than evolving an escape from fire, runner oaks acquiesced to the inevitable and regularly sacrifice their above-ground parts to fire. This makes more sense once you realize that most of their biomass is underground, immune to fire, and the incineration of the stuff above ground merely leaves behind ash to fertilize the regrowth of new sprouts from the dense fabric of underground stems.

But look around--- runner oak isn't the only flatwoods plant that lives this way. Pull up a few gallberry, or shiny blueberry, or gopher apple, or lyonia, or backen fern, and you will see that they are all clones springing from a fabric of dense underground stems from which they regrow after fires.

These clones spread more like bacterial colonies, or mold on a jar of jam than seed plants, advancing on visible fronts like Napoleonic armies. When fire is as frequent as every one to three years, these armies cannot advance from their wetland margin bases, and the fast-recovering bunch grasses hold the field. Natural fires in the piney woods were started mostly in the spring “lightning season” when thunderstorms were frequent, but rain was not. These annual fires burned until the summer monsoon rains extinguished them.

But with the reduction of fire frequency under human management, the gallberry, fetterbush and their ilk have marched upslope from the wetland margins, while the shiny blueberry, gopher apple and runner oak have marched downslope to clash and intermingle along wide fronts. It is a slow-motion war, a slow conquest played out over decades, the main losers being the grasses.

In a landscape that is scorched over and over, year after year, the only sensible thing to do is to retreat to the bomb shelter underground. In the flatwoods, everybody does it, and it is not laziness, it is the only hope for survival.

Fascinating observation and written piece on adaptation……and other living groups follow the same pattern: unable to build an edifice, they disperse for survival, yet keep connections.

Great essay about adaptation Walter. So much of life (including in my field of human behavior) is happening "underground" and hidden from sight. Very clever cloaking maneuver!

BTW, your botanical drawings are really excellent! 👏