Some years ago, I got a mail notice to appear for jury selection at the county courthouse. The letter assigned me a particular time and date, along with a threat of what would happen to me should I not appear. Being a naturalized citizen, I naturally considered it my duty to comply with the summons, and to serve on a jury with my peers. I’m not sure I could have put my finger on exactly who my peers were, but I was pretty pleased that I had been called. After all, I knew some stuff, and wanted to put it to some use for the good of the general public.

So, on the appointed day and time, I ambled into the county courthouse, and was directed by the receptionist to Room C. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that Room C was already packed with my peers of a wide range of descriptions, sizes, and ages.

After some time, an employee of the county clerk came in and gave us a lot of instructions, information, and inspiring reasons why we were here. This was followed by some questions to which some of my peers responded, upon which the clerk said you are excused from jury duty and can go home (or wherever). We remaining peers then waited some more until another clerk announced that jurors with numbers x to z were to proceed to Courtroom 3 where we were to be screened for our suitability to serve on a jury involving a civil case.

My number was between x and z, so I tagged along with the group. This was gratifying because I had been summoned several times before and then sent home because the court had all the peers they wanted. Perhaps this time I would get to do my citizenly duty! Hope glowed on the horizon.

A couple of lawyers came in bearing folders and brief cases and wearing lawyer suits, and a couple of minutes later here came the judge in his black robes. This being America, he wasn’t wearing a powdered wig. Everybody got settled, and then the judge, from his elevated bench, welcomed us prospective jurors and said we were shortly going to start voir dire, whatever that meant. He then described the case we might be asked to decide, a homeowner’s suit against a tree service asking for compensation for bodily injury. Apparently, the homeowner wanted to see how the removal of one of his trees was coming along, and went out to look, standing under the tree in which the climber-cutter was cutting and dropping sections, starting from the top (where else could you start from, eh?). So, while said homeowner was gawking, one of the sections hit and injured him.

At this point, I hoped that I would be asked to serve so that I could let the court know that anybody dumb enough to stand under a tree from which sections were being dropped did not deserve compensation. As they say, it’s not rocket surgery.

The lawyers for both sides now called up each prospective juror, questioning them about the usual “Are you brave and honest”, but also “How much do you know about the cutting and climbing trees.” Listening to these questions, my opinion of how valuable a juror I was going to be began to rise, and I was looking forward to my turn.

After I answered that I was going to be brave and honest, and tell the truth, the lawyer asked, “Have you ever cut down a tree?” “Yes”, I said. “What’s the biggest tree you’ve ever cut down?” “Well”, I said, “about two and a half feet.” He replied, “tall?” “No”, I said, “in diameter at breast height.” His eyebrows rose, so this was clearly not what he expected, but he plowed ahead. “So, this means you know how to use a chain saw, right?” “No, I replied, “I don’t use a chain saw.”

At this point, the judge, whose mind had clearly been drifting, sat up, looked around the courtroom and said, “I think everyone in this room will be interested in learning how you cut down a 2 ½ foot diameter tree without a chain saw.”

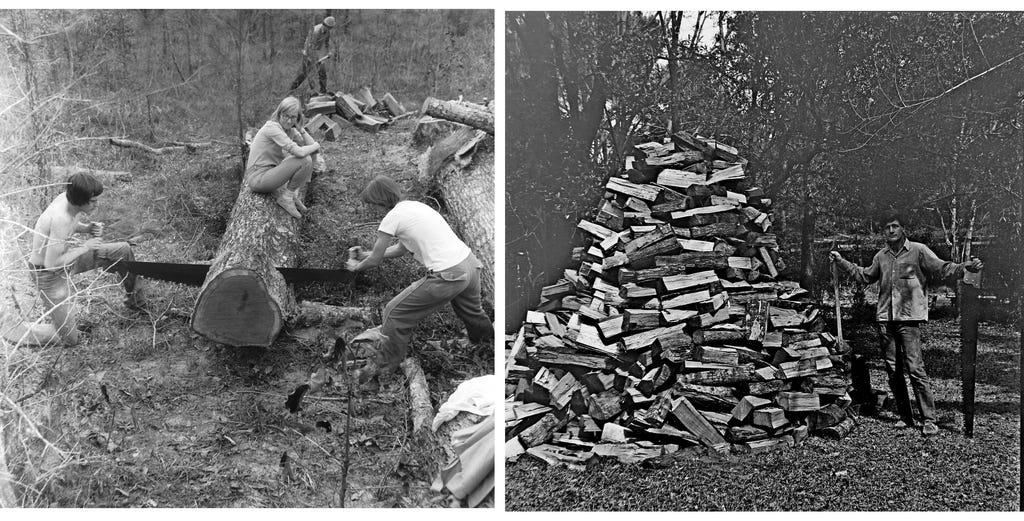

I waxed to the challenge. “Your Honor”, I said, “I use a six-foot-long, 19th century, thickback saw that I got from a barn in Ithaca, New York. It’s got a handle on each end, and I get on one end and a friend gets on the other and we pull it back and forth, and pretty soon, down comes the tree. And then we cut it up with the same thickback saw, and that’s easier because you are cutting vertically then. Your Honor, I cut all my firewood with my thickback saw. With the help of my friends, of course. And then I split it with a big maul and stack it in my woodshed” (I began to sense that this was a bit beyond what the judge wanted to know, so I stopped explaining).

For some reason, there was considerable tittering in the courtroom, but I clearly had the judge’s interest.

Apparently, the lawyer hadn’t yet been impressed enough by what a really swell, informed juror I would be, and he asked, “Have you ever climbed a tree?” “Sure,” I answered, “many times.” By now, he should have known better, but he continued, “Well, what’s the tallest tree you’ve ever climbed?” I thought for a moment, trying to remember all the trees, and recalled a particular fir tree in the Sierra Nevada that was easy to climb because it had regularly spaced branches all the way to the ground. I said, “I’m not sure, but I would say, well over a hundred feet tall.” I could have added, And the view was great!

The lawyer’s brow furrowed in what I thought was probably admiration, and he said, “Can I ask why you climbed this tree?” “Sure,” I replied, “I wanted to see what it looked like from the top.” I didn’t reveal that I was following the example of John Muir who climbed a tree in a howling Sierra storm to see what it felt like to be a tree in a howling Sierra storm. I didn’t want my climb to seem unoriginal.

From the stirring in the courtroom, I could tell that everyone was impressed. After everyone had settled down, the lawyer said, “I have no further questions your honor.” And then he added, “Your Honor, I ask to have this juror dismissed.”

I was stunned. I had just shown that I knew a lot about cutting and climbing trees, along with the how’s, why’s and wherefores, and I was ready to render an informed opinion about how dumb it was to stand under a tree from which a guy dangling from a rope and swinging a blazing chainsaw was dropping sections of trunk thicker and taller than a man. My view of the jury system took a nosedive as I exited the courtroom in confusion. I have always believed that a person can’t know too much, but I had just been told that actually, a person can indeed know too much, and that disqualifies him from a jury.

Since this little adventure, I have often wondered how the jury decided this case. Did they reward the homeowner who was dumb enough to stand under the tree while pieces of trunk tumbled to the ground around him, or did they find for the tree service that was doing what they were paid to do? Depending on the answer, my faith in the jury system could either be restored or take another tumble like a piece of trunk dropped from a treetop.

Friends are asking how the case was settled. Any idea?

In my limited potential juror experience, lawyers are always wary of people who know a lot about the actual experiences related to the case because that may not "work" with the legal issues. One should not confuse intelligence and practical involvement with the law.