Sweetness

A taste, both sweet and dark

Chemical names may be precise, but they are often also cumbersome, so chemists often give common chemicals common names, and when the chemicals are derived from plants, the plant is honored by naming the chemical after it. Witness, nicotine from Nicotiana tabacum, caffeine from Coffea arabica, ephedrine from Ephedra sinica and so on. Thus it was that upon seeing the European mountain ash, Sorbus aucaparia, in London's Hyde Park, I thought of the sugar sorbose and its alcohol derivative, sorbitol that is often used as a low-calorie sweetener and thickener. Doesn't everybody? Doesn't everybody associate the sugar ribose (as in deoxy-ribose of DNA) with the currants or gooseberries of the genus Ribes? Galactose conjures up thoughts of milk, mannose thoughts of manna, not from heaven, but from the excretions of cicadas on ash trees, zylose the hydrolysis of wood, arabinose gum arabic. Then there is the generic fructose conjuring many fruits, and glucose from the Greek meaning grape juice.

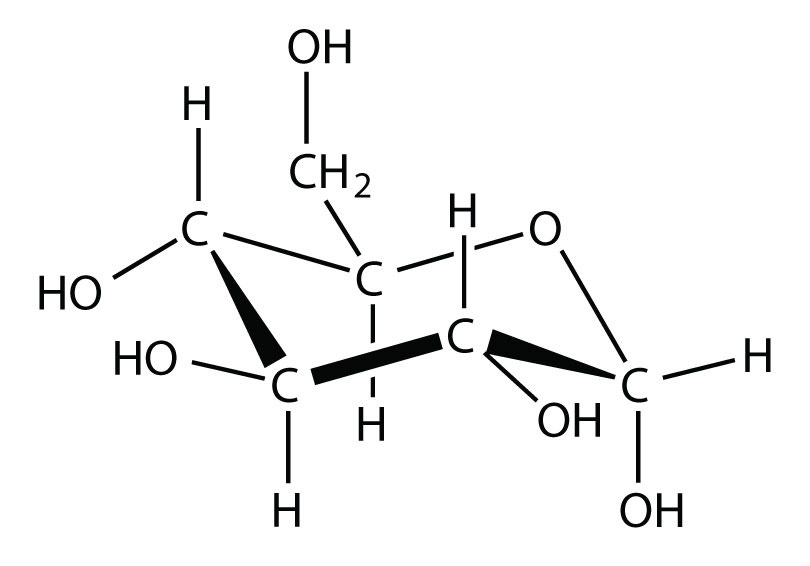

Most of these compounds fall under the term “sugars”, a class of chemicals we associate with sweetness. Their sweetness varies with the details of their molecular structures and chemistry, and is a study in subtle complexity, for while sugars mostly conform to the carbohydrate composition (one carbon atom per H2O, hence the name carbo-hydrate), they can have anywhere from 4 to 7 carbons, although most have 5 or 6. The ends of the sugar molecule are reactive, and most bite their own tail to form a ring, but the ring is usually not flat but puckered, and the direction of puckering changes the chemical and the physical properties quite a lot. What's more, the reactive groups are themselves chameleons, capable of switching from one reactive form to another. All this was really cool stuff when I first learned about it in organic chemistry, and it still is.

The chemical virtuosity of sugars is such that they can join together in twos as in sucrose (below), in threes, or in long chains that we know as starches, the chief energy storage compounds of the living world, and cellulose, the chief structural material of the plant world.

For us, sugars are all about sweetness, a taste that we humans love because of our frugivorous ancestors, but cats don't even detect. Natural sugars vary in sweetness by less than 20-fold, with fructose at the top. We sense sweetness when a molecule, normally a sugar, interacts with a particular kind of protein taste receptor on our tongue. But these receptors can be fooled, and many compounds, both natural and synthetic, some toxic, some not, can trigger these receptors to produce a sweet sensation in the brain. Why some molecules are sweet is not well understood, but it probably involves how the shape of the molecule fits the shape of the business parts of the receptor protein--- if the fit is good, the receptor goes into ecstasy and does its work, triggering a response in the sensory cell that speeds its way to the brain, eliciting a "yum" in the owner of the cell. By decoding what these receptors “like”, organic chemists have made many artificial sweeteners that are sweeter than sugar, with the sweetest of all being over 200,000 times as sweet. The sorbose from my Hyde Park tree can't hold a candle to this super-sweet fake, but at least it can be metabolized, and the berries are pretty.

But sugar also has a long and dark history. In premodern Europe, it was a rarity that only royalty could afford, offered to guests in silver boxes or made into figurines to decorate sumptuous dinner tables and show off wealth. My grandfather, an officer in the Austrian Army during the Russian siege of the fortress of Przemyśl, Poland in WW1, did some favors for a Polish nobleman, and was rewarded with a choice of anything he wanted in return. He chose the 17th century silver sugar box below. The fact that it is sterling silver alone suggests the value of the sugar it contained, but the fact that it locks with a key is surely convincing evidence.

Before the discovery of the New World, the source of sugar was mostly from southeast Asia where it was derived from sugar cane, a tall grass with sweet stems first domesticated in New Guinea a very long time ago. With the discovery of the Americas, Europeans established sugar cane plantations in the Caribbean and South America, making sugar gradually more available and more affordable. But cultivation was labor intensive, and that labor was provided mostly by slaves from Africa. The human love for sweet things, along with declining prices made sugar into an essential staple commodity extracted from the colonies through the misery of African slaves. The economics of sugar created huge fortunes that paralleled political power and made the sugar-producing American colonies essentially extensions of European economies, a kind of off-shore forced-labor farming that probably wouldn’t have been tolerated on-shore. Sugar, along with several other slave-produced foods including coffee, tea, and cocoa changed European culture greatly and forever. All came together in coffee shops and tea salons.

I have traveled in several tropical countries in which sugar is a major (mostly export) crop. Indeed, it is grown in most tropical countries with suitable soils and climates, and the scale has been enormous for several centuries. On a visit to my brother, as my plane approached the airport in Georgetown, Guyana, sugar cane polders built on tidal land lay below me as far as the eye could see up and down the coast. Each polder was surrounded by dikes and gated canals to keep the sea out at high tide, to irrigate the cane from upslope, but also to allow boats to load harvested cane from downslope canals connected to the river. These enormous and ingenious earthworks were built by hand by African slaves under Dutch masters when Guyana was a Dutch colony. The Dutch applied their experience in creating polders in their native Netherlands to create these cane polders in South America, polders that are still in use almost 400 years later. After the slaves were freed, part of the labor was provided by Indian indentured laborers, and today, the population of Guyana is about equal parts African and Indian in origin with a small minority of white Europeans thrown in. Were it not for the European greed for sugar, what would Guyana look like today? Would it even exist?

After his time in Guyana, my brother spent the last two decades of his life in Guatemala in a small agricultural town on the Pacific slope, in the shadow of several volcanoes whose menacing, smoking silhouettes made up the eastern horizon. Here too, sugar was a major export crop. The volcanic soils in the area are some of the most productive in the world for growing sugar cane. When it is time to burn the foliage off the cane before harvest, the whole region turns smokey grey, and during harvest time, it is scary to drive the two-lane roads as huge, tandem-trailer trucks with multi-ton loads of cane roar past on their way to the mills.

With my brother, I toured one of the sugar mills near his town. These mills are huge, modern industrial factories that crush the sweet juice out of the cane, burn the resulting fibrous waste to boil off the water from the juice until sugar crystallizes out, ready to be spun dry in centrifuges leaving behind the thick brown molasses.

The mill produces sugar to the specifications of major buyers, adjusting color and crystal size through careful recrystallization, and storing the resulting dry sugar in mountains in warehouses until it can be loaded into the hull of ships to be sent to their destinations around the world. Depending on the country, it may then be recrystallized again to produce the pure white, very fine sugar often preferred by consumers. It is a very long way from keeping sugar in lockable silver boxes.

Today sugar is consumed in enormous quantities in every food imaginable and some not imaginable, and is associated with an epidemic of obesity, diabetes and other health problems. Could this be slavery’s payback? It seems unlikely, for the descendants of the slaves who once produced the sugar are themselves victims of these health problems.

Ah sweetness! Our ancestry of fruit-eating primates has made us fools for the sweetness of sugars, but the pleasant sweetness of fruit was not enough, and we sought out ever more intense sweetness, leading eventually to the isolation of sugars in pure form and enormous abundance. As pleasurable as this has been, our sensory quest has had consequences. The addiction to sweetness that once guided us to our food, has lead to entire economic systems, created new countries, created huge health problems, given pleasure to hundred of millions and made the lives of other hundreds of millions miserable and short. We must ask, is the pleasure we get from sweetness really harmless?

An interesting and informative history of a product of human gluttony and greed, the exploitation incurred and endured. As usual very well written.

A well-nigh perfect essay. I can't imagine any bases you didn't touch on! After I write this comment, I'm going to re-read it, especially about the polders of Guyana.. Amazing.

As usual, your art is also wonderful!