Note: I wrote this essay after a long visit to South Africa in 1998, four years after the end of apartheid.

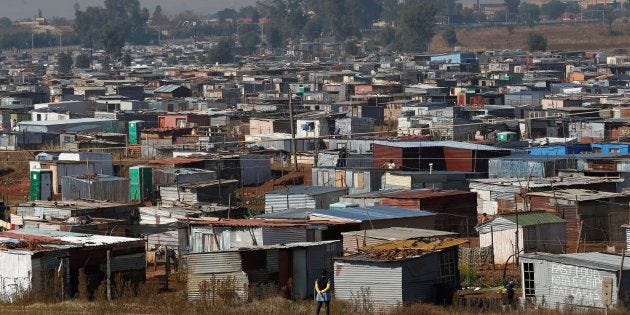

In the New South Africa, the levees constructed of national borders and the laws of apartheid have ruptured and the populations that they held in place are sloshing and flooding in staggering numbers with alarming consequences. On the perimeter of every city, or even small town, on any unguarded land, squatter-towns spring up, often literally overnight. Even in the townships, those black enclaves enforced under apartheid, the neighborhoods of “real” houses are often flanked by squatter shacks of discarded packing crates, mismatched sheet metal, flattened cardboard boxes, broken planks, rocks torn from the ground, and chipped concrete blocks, like the rubble that accumulates around a house under construction. There was a time when the old government periodically bulldozed such collections of squatters’ shacks, only to have them spring up again when their backs were turned. The New South African government can’t possibly use such methods.

It is hard to imagine oneself as a squatter. What uproots people and moves them to live in squalid towns of cardboard and mud? Is it hope, or despair? Both in alternation, depending on the weather? Is it better than where they came from? Other questions suggest themselves. Squatter camps look chaotic without a discernible square grid line, but are they? Surely family is an organizing force, even in squatter camps? People tend to recreate familiar patterns whenever possible. Do squatter families recreate the family kraal in tar-paper and corrugated metal? And how is the vast amount of material used in construction transported to these inconvenient locations? On peoples’ backs, one piece at a time? Vehicles are almost absent from most squatter camps. Food and water travel in bags and buckets. You don’t even want to think about sewage.

Sometimes squatting is a raw land-grab. In its land-invasion form, organizers spread the word to be ready to squat on a targeted piece of land on a specified day and time. A farmer may kiss his cows good night, and dream of his sweet, life-sustaining farm, only to wake in the morning to the nightmare of several hundred people squatting on his land. He is powerless to evict them, and the police are useless. His animals disappear into the squatters cooking pots, and his crops are trampled or stolen. His fate is almost invariably to lose his farm to this organized onslaught of the landless. The outskirts of Johannesburg and Pretoria are dotted with abandoned farmsteads, their buildings burned and gutted, any usable material long carried away to build the nearby squatters’ camp.

The farmers’ primary weapon against land-invasion is the cellular telephone. The moment squatters are spotted, the call goes out to neighbors who converge to evict the squatters, with force if necessary. Ugly confrontations are common. It’s hard not to have sympathy with both sides.

Before it gained power, the New South African government made the rash promise that it would house all South Africans who needed it. Perhaps they did not anticipate the staggering population movement that would follow the end of apartheid, the hundreds of thousands of uprooted people converging on the cities, the pent-up urbanization stifled by Old South Africa. Nor could they anticipate the flood of immigrants, legal and illegal, that would surge into South Africa from Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique and countries further north, to escape crumbling economies and political chaos, looking for hope south of the border. South Africa’s borders with its neighbors are imaginary lines drawn in the sand. Defending them would require the dedication of a lot of manpower and treasure. By comparison, our border with Mexico is the Great Wall.

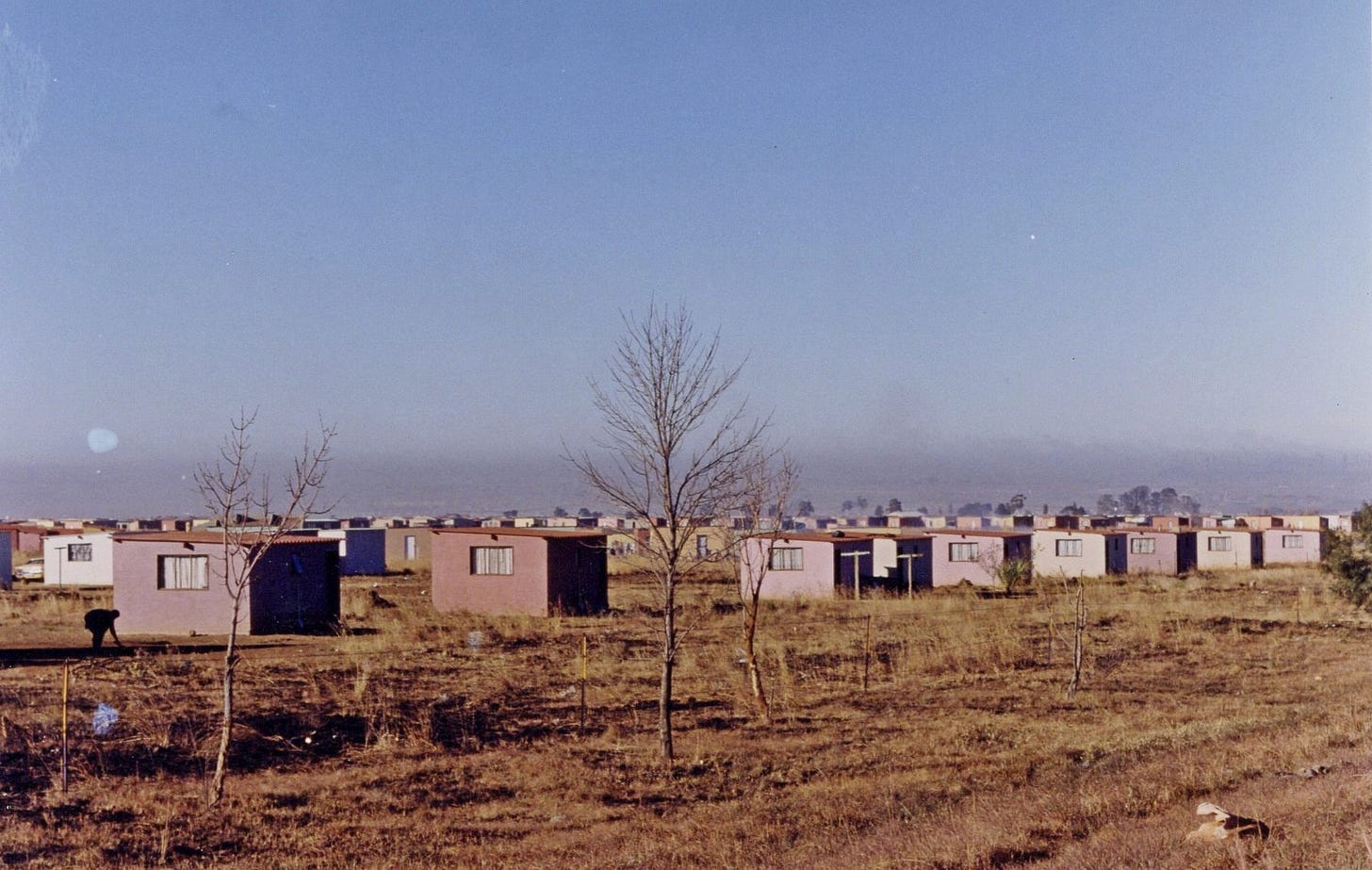

On the perimeter of Johannesburg and Pretoria, the government’s scramble to fulfill the promise intrudes dramatically on the landscape. Vast tracts of one or two-room, concrete block houses arranged in neat grids, and painted bright colors crowd the freeway and fade toward the distant horizon, dim colored dots on the distant hills. These are the government’s version of squatter camps, but there is at least minimal sanitation and there are water lines, at least to neighborhoods, and there are streets. What is missing is the self-organized, organic arrangements of the squatters’ camps, with their (I assume) reflection of social relationships, their ghosts of family kraals. Surely, the government’s effort puts a roof over people’s heads, but does it serve to organize communities in meaningful and functional ways? Or are these towns tomorrow’s dysfunctional slums? Most lie well outside the urban perimeter on yesterday’s farmland, an hour or more on foot and slow bus from any work at all. It can make an 8 hour a day job into a 12 or 16 hour undertaking. It has long been thus in South Africa, and there seems little promise of change.

And still the people come. In spite of the cardboard-box living, in spite of the lack of work, in spite of leaving their homes, the squatter towns grow from industrial jetsam and flotsam and from the refuse of a wealthier class.

But every flood must end. The water gives up its energy, the current slackens and the torrents slow and pool. The water stands on the land, gives up its silt and permeates into the soil. A flood’s legacy is not simply to have swept away, but also to fertilize for new growth. The irresistible flood, be it water or people, eventually spends its force and creates something new. Perhaps the shantytowns are the first green poking through the silt. Perhaps they will bind the people to a new place, and like a forest reclaiming a sandbar, in successional stages, they will be transformed through material accretion, through sweat and hope, and slowly, they will become permanent towns.

Thought-provoking read, Walter. Informative and lyrical!!

An excellent essay in my estimation Walter with a quite poetic ending.