When you do research on fire ant biology as I used to do, your choice of habitat tends toward the buggered and disturbed, the places that people have reduced to an early stage of succession like pastures, roadsides, or lawns, for fire ants are creatures that follow human disturbance like day follows night or the tail follows the cat. And because to do this research you may need to mark colonies, or put traps over them, or do other things that are visible from the road, you need a place that is nasty to trespassers, be they simply curious, felonious, or magic mushroom collectors. Otherwise, you are inviting vandalism that can put your whole project in jeopardy.

Thus, Southwood Farm, a patrolled, 8000-acre cattle farm outside Tallahassee, was home to my fire ant research for almost 30 years, outliving three managers. Its pastures were as much home to me as they were to thousands of fire ant colonies. It was a place of rolling pastures and spreading live oaks wider than tall, of ponds, assorted bits of woods, dirt lanes, conservation terraces, fences, and gates in various states of decrepitude. The Big House was where the eccentric owner, Ed Ball stayed on his visits, and was off limits to us. On every visit, we always checked in at the office building, where the secretary, Stella of the Big Hair read catalogs all day and did her nails. We'll be in the east pasture, I would say. OK, she responded, and went back to her shoe catalog.

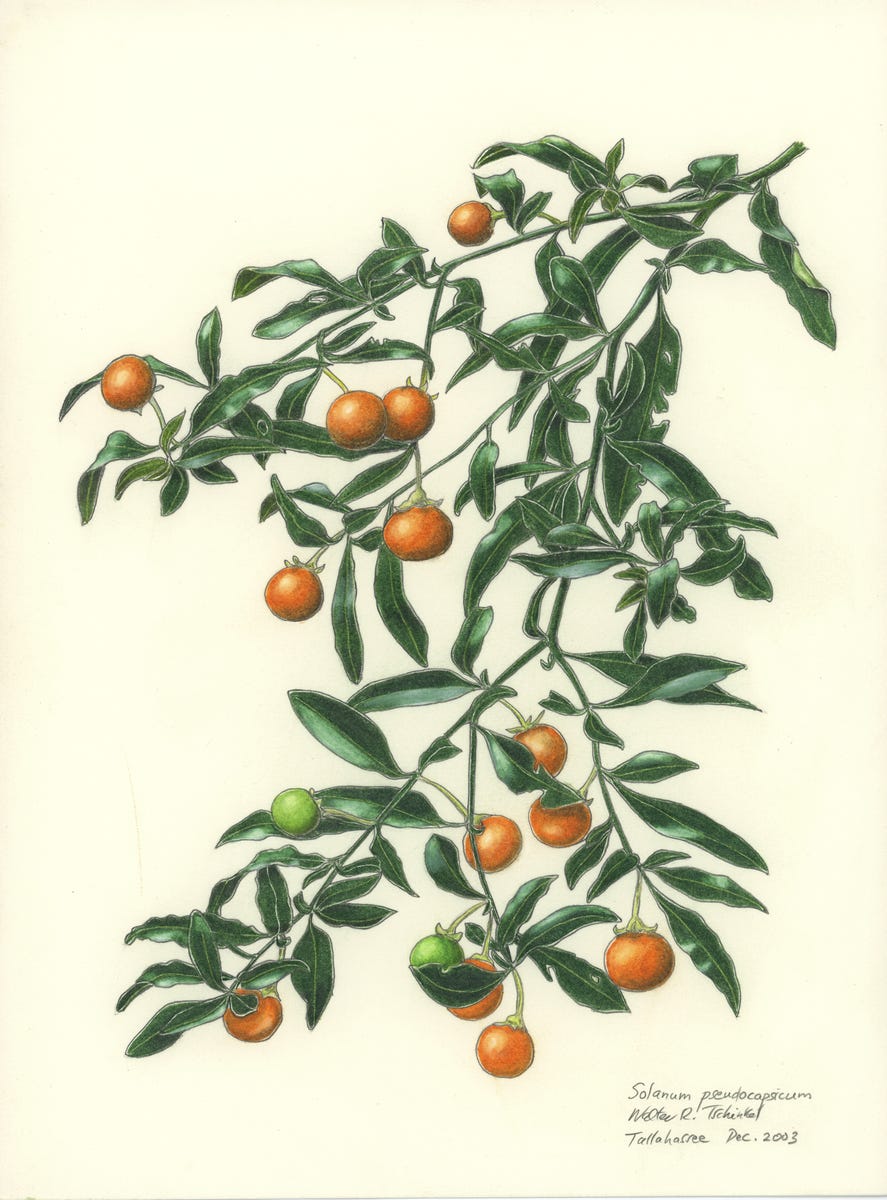

Our days were filled with mapping and tagging more than a thousand colonies with numbered aluminum tags, capturing queens, sampling workers, and retrieving trapped sexual ants. On hot summer days, the grand shady live oaks offered a lunchtime respite from the sun, and we shared the shade with dozens of dark-leaved Solanum pseudocapsicum shrubs with their shiny red tomato-like fruits. The resemblance was not accidental, for like the tomato, they were in the nightshade family. They flourished on the abundant cowpies left behind by the cattle who also sought the oak's shade as respite while chewing their cuds. The shrubs were there year after year, cheerful and healthy looking, so eventually I dug a few up to transplant to our yard where they lived several years before finally expiring of old age.

I later learned that S. pseudocapsicum were immigrants from Peru, but at Southwood, they were far from the only immigrants, for pasture is the infant of ecosystems, friendly to fast-growing, short-lived immigrants from all over the world, and straining to grow up to be a dense, dark forest full of oaks, beeches, magnolias, and pines. To keep pasture in its baby stage requires regular "bush hogging" (mowing), because cows shun many of the exotic and native interlopers staking an optimistic claim in the pasture. Acorns from the live oaks along the fences somehow find their way into the pasture to germinate, as do thousands of seeds from the loblolly pines. Blackberry tangles reward us with berries in spring, and dog fennel shoots its frilly white spears upward. Possums crossing the pasture leave their defecated presents of persimmon seeds, and young persimmon trees are sprinkled generously. The fate of all these hopefuls is to become bonsais after repeated mowing. Occasional coyotes wander the pastures, then silently disappear again, and armadillos browse on our fire ant colonies.

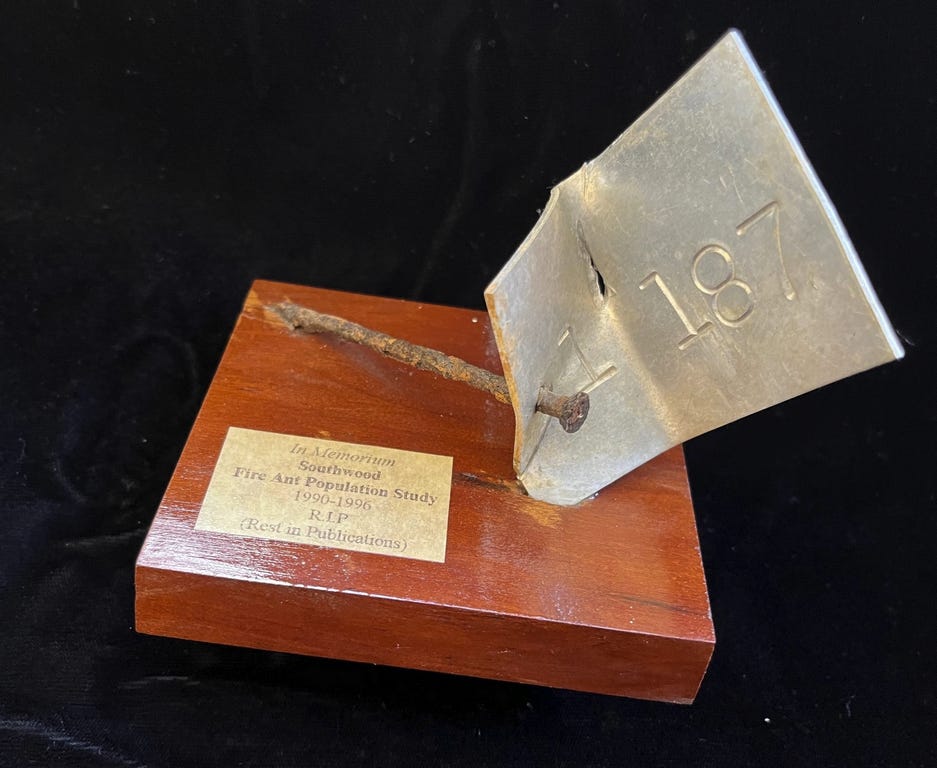

I have never quite decided whether the end of our long-term fire ant population study was poetically appropriate, but one day, one of the farm's employees on a tractor bush-hogged the entire field--- pines, oaks, persimmons, and fire ant colonies. Fire ant mounds whose volume we measured four times a year to reveal how many ants made up the colony were scattered and flattened. Our numbered aluminum tags were yanked from the ground and sent flying, and vinyl flags were tattered and turned into wire pretzels.

I recovered one of the bent and ruptured aluminum tags, and on a wooden base, I made a little memento of this daunting study and titled it R.I.P. (Rest in Publication). Sadly, much of what we learned about the population of fire ant colonies, although included in my book, The Fire Ants, was never published in a peer reviewed paper, and is thus not often cited in papers. Although my colleague, Eldridge and I made efforts to publish this work, Eldridge's interests had drifted to how sheep dogs and sheep form self-organized entities, analyzing the motion of both from movies taken from tall towers. Sadly, Eldridge died of cancer before we were able to publish our results. Science lost a brilliant ecologist, and the fire ants lost a bard to tell their tale.

The fate of Southwood Plantation was to be sold off for a gigantic development complete with golf courses, endless lawns, and sanitized ponds, another victim of corporate development. Gone were the scruffy pastures, the sagging gates, the dirt lanes, the coyotes shining in the morning sun, and the cows resting under spreading live oaks among the Solanum pseuocapsicum. In their place there arose a sterile suburb with a choice of model houses, and apartments, with paved streets and yellow lines, endless driveways, repetitive swimming pools, clubhouses, and an infinite supply of cars. But then it comes to me--- Southwood Farm was once a mature forest of pines, oaks, magnolias, and a dozen other broadleaf trees. The pastures that were so congenial to the fire ants, the cows, and to me were already, from the forest's point of view, severely altered from what nature had put there, beaten down to our desired purpose.

I have never returned to Southwood, for most of what I knew is gone. Should I mourn that magical, enjoyable, and productive part of my life? Perhaps, and sometimes, mourning seems the right thing to do. But in a life as long as mine, there is much to mourn, but also much to celebrate. Southwood is celebrated vividly in my memory, and that celebration is enough.

thank you, Walter -- this is so sorrowful (not sure about the grammar here - but it makes me feel so sorrowful) And the live oaks-- there was a big ol' one at the farm of my relatives outside of Gainesville, on their sandy-soil homestead that didn't grow much of anything. But the live oak was live to we kids and we could be lifted up by a daddy or uncle to sit on the lowest limbs. I however, knew as a 5-year-old that if I stood up straight and then whirled in place - like a bare-foot ice-skater -- that in fact I would fly up and plump down on the lowest branch. I never told anyone about this power - the menfolk were around -- but always knew I could, and know it to this day. A Live Oak Legend!

Evocative and beautiful account, with some lessons in it for all of us. I'm Restacking this to Notes so non-subsribers can read it.