I know I’m not supposed to assign human attributes to animals. After all, I taught Animal Behavior for 40 years and often hammered that point home. And yet, there are times when the behavior of the animals so clearly invites human comparison that you just say, Oh, what the hell!

Of course this is commonplace between people and their pets. Note also fierce lions, smart foxes, cuddly koalas, and so on. It was seeing the behavior of sand grouse (plural: sand grice?) at a waterhole in the Namib Desert of southwestern Africa that finally made me relent and say, Oh, what the hell!

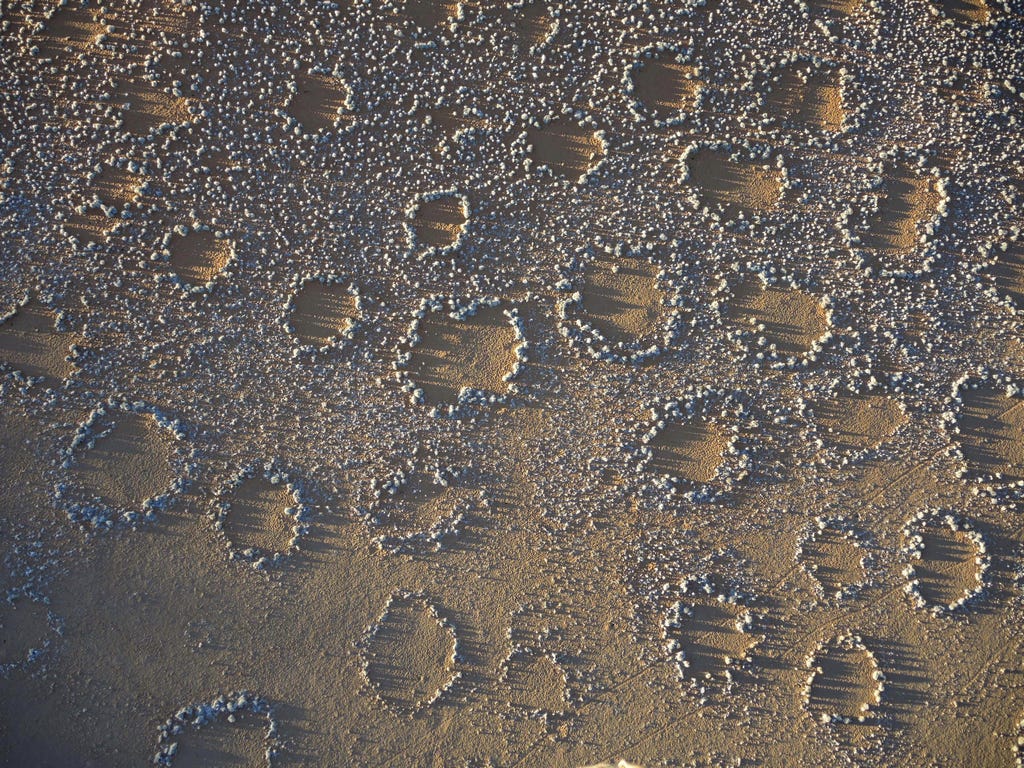

We stayed in the guest house at Keerweder, the ranger station of the Namib Rand Nature Reserve while we investigated the “fairy circles” that are such a conspicuous feature of this desert. With considerable effort and patience, you can find Keerweder on Google Earth, for it is just a little fenced patch of desert with a few buildings in a vast landscape of sand seas, jumbled, weathered granite hills, and dark, broken mountains. The patch contains some dwelling buildings and some work buildings, a few ornamental plantings, and a guest house for visiting scientists and assorted dignitaries. Two small bedrooms, a bathroom, a kitchen, and a covered porch where you can sit in the shade, feel the desert wind, and enjoy the antics of the striped mouse residing in the woodpile.

Better yet is that from the porch, there is a clear view of the station’s “water point” that serves the Reserve’s abundant wild animals, including oryx antelopes, hartebeest, springbok, ostrich, and an assortment of smaller or nocturnal critters. While we had our ritual morning coffee or tea on the porch, sand grouse gathered at the water point by the hundreds for their own morning ritual . Small groups fluttered in on whirring wings, then wheeled a bit as they approached, before settling in a stirring of dust twenty meters to the left (from our viewpoint) of the water, the crowd growing and growing as more grouse arrived from parts unknown to participate in this morning ceremony. Watching this ritual every morning, I couldn’t resist describing these birds as “polite.”

They had obviously come for the water, but this was not an unruly “I-was-here-first” crowd, or even an “I-just-came-for-the-water” crowd. No indeed, before “The Taking of the Water,” it was necessary to have the Meet-and-Greet Ceremony, each grouse walking at a stately pace, chucking and clucking greetings as they milled around, the avian equivalent of a “how-are-you-today?” with an occasional “nice-weather!” tossed in. We, the ritual coffee drinkers on the porch were watching an important grouse morning ritual, but in contrast to our two participants, the grouse had several hundred walking around with their heads held high and their feathered chests leading.

Like all parties, this one had to stick to a schedule implicitly understood by all, but there was also a hierarchy of who was to make the moves that kept the proceedings on schedule. And sure enough, there they were, one in the lead (the host?), with three or four following closely, breaking from the crowd and heading for the water. Soon the center of gravity of the party shifted as more and more grouse followed the lead of the “host grouse” until the crowd of grouse flowed like a fluid in the direction of the water.

But even then, politeness ruled the day, for none of the grouse rushed to the water. No, they gathered again a short distance from the water, politely chatting and milling while they waited patiently for their turn to Take the Waters.

And still, politeness reigned, and you could almost hear the grouse saying, “No, please… after you,” as the first wave walked into the water up to their breasts, drank their fill, then fluffed their feathers a bit to capture a load of water in their specially-modified breast feathers, then took to the air in a whir of wings. One wave after another waded in and loaded up, then took flight in small groups, wheeling upward and breaking up gradually as individual grouse headed back to their scattered nests somewhere in this vast desert, possibly many miles away, all with a spouse and chicks awaiting their return. Having arrived at their nests, a shallow disc in the sand, the parent grouse (more often the male) would be offering the water in its breast feathers to the chicks and the spouse. In this way the grouse can breed miles and miles from any water in this otherwise waterless land.

As essential as this water is to the grouse, there is no pushing and shoving, no rudeness, no “me-first,” no “get-outa-my-way.” No, these are birds with real manners, polite birds, birds with fine breeding. And as in human society, politeness allows diverse individuals to come together in peace and relative harmony to share a life-giving resource.

There seems little doubt that sand grouse discovered the value of politeness long before humans did. I also guess that they violate the rules of politeness much less often than humans do.

I don't think I could resist feeding the striped mouse! The sand grouse while not so winsome displays astonishing courtesy and cooperation. I wonder if anyone has done a book.ob them?

Your observations are very interesting. Do you think that if the water supply was more readily available to the grouse, they might have dispensed with their deference to one another?