I was a wartime baby, having been born in 1940 during WW2 in what was then Greater Germany (now the Czech Republic). Looking back on it, I didn't choose the most auspicious time to be born. These were hard times for millions, and catastrophic to lethal for millions more, but in spite of hardship my family survived intact, eventually settling into a new life in the USA. Although I remember bits and pieces from these war years, I was a little kid, so none of the anxiety and responsibility fell on my tiny little shoulders. But growing up, The War was always a background to the history of our family, and for that matter, to that of all my German friends. It was just there, always lurking, surfacing every once in a while, in offhand comments, stories of hardships, joys, longing, relief, survival or loss, and it shaped attitudes and imaginations, inevitably including mine. For many of us German wartime children, The War seeped in to occupy some, perhaps unacknowledged, corner of our personas.

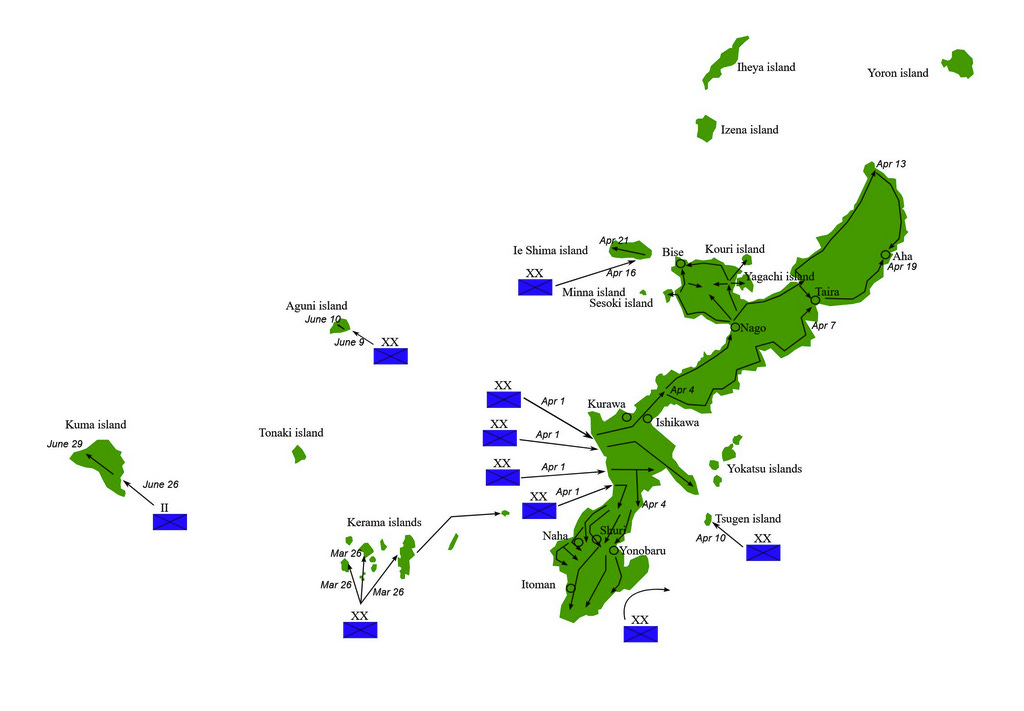

So, when I arrived in Okinawa for a workshop on Multi-scale Phenomena in Biology, I looked upon the landscape passing by my taxi window and saw, not the oriental tourist paradise of today, but what must have been the frightening hell of an American invasion and Japanese defense during the closing days of World War II. The Battle of Okinawa followed an enormous amphibious landing, and raged for 82 days as the most ferocious battle of the Pacific War. It was a battle fought by almost a quarter of a million American soldiers, defended by about 110,000 Japanese soldiers, of which 30,000 were Okinawan conscripts. The desperate Japanese launched over 1500 kamikaze attacks, forced thousands of Okinawans to commit suicide, and conscripted children 14 to 17 years of age, most of whom died. Hundreds of ships were sunk or destroyed. When the rains came as the battle went on, mud impeded movement and even the recovery of bodies, and the island became a land of maggots. By the end, Americans had suffered 83,000 casualties of which 12,000 were deaths, most of the Japanese defenders and almost half of the native Okinawan population of 140,000 were dead. In light of the human and material cost of the battle for Okinawa, the looming invasion of the Japanese mainland and its expected cost probably convinced America to unleash the atomic bomb to force Japanese surrender.

Okinawa is a mountain range poking out of the ocean, surrounded by corals and lacerating, rocky shores. What it laughingly tries to pass off as a climate is a dripping, saturated blanket of soggy air, relieved now and then by flaccid, soggy breezes from the sea.

I left the frigidly air-conditioned hotel with its fogged windows and headed up some side-roads into the hills to explore the native flora and fauna. It was southern California all over again, with almost nothing native to be seen. The main difference was that here my sweaty shirt stuck to my skin. On the edge of the walkway leading along the cliff top grew a dense, flowering vine with the faint odor of garlic and a purple, tubular flower. It looked like trumpet vine with purple instead of orange flowers, an unmistakable member of the same family, the Bignoniaceae. Standing in the sun with my sketch pad and pencil, I feel the sweat trickle down my back into my underwear, and maneuver to keep from dripping onto the paper. Below me sharp coral rocks protrude from the water, and 200 meters from shore the surf foams on the reef. My mind's eye sees sweating soldiers manning watch stations or shore batteries in the unbearable heat, American marines sweating and seasick on pitching landing craft heading into a lethal hailstorm of fire, Okinawans by the hundreds committing suicide in caves.

What must it have been like? Imagination fails. Sketching my garlic vine on the cliff top, the reef offshore, white and foaming today as it must have foamed then, the island is mute, and most of the witnesses are long gone.

I got an emailed comment from Lynn Rogers and asked if I could share it. So, here it is.

Interesting story and description of Okinawa.

I was named after my uncle, Lynn Hunter, who was a Marine off Okinawa waiting to land on the beach at the southeast shore. One morning they were given a good breakfast and then they climbed down and loaded into their landing craft. As they approached the shore, they could see Corsair fighter planes strafing the shore line and dropping bombs to create smoke. He said you could see the Corsairs shudder as they fired their machine guns and see them slow down from the recoil. He kept getting closer and closer to the beach and then all of a sudden they were told to turn back. They didn’t understand what was going on. No one told them and the next day the same thing happened again. They approached the beach and then were told to turn around and come back. The third day this happened again. Then, with no explanation, they were sent back to Saipan. He found out years later that this was all a fake attack in hopes of pulling the Japanese away from the actual attack area. In late August 1945, at the age of 19, he was sent to Nagasaki to serve as an MP for a couple of months. This was just a few weeks after the atomic bomb was dropped there. He lived to the age of 92 with no apparent effects from radiation.

Lynn Hunter Rogers

Walter, good research on the Battle of Okinawa. It was, like so many of the island battles "Hell on earth". I had an uncle who fought with the army on Guadalcanal and and another who was with the Marines and was wounded in the first assault wave. The real tragedy is not so much those battles, as tragic as they were, but the lamentable fact that we have learned nothing in the last 90 years.

Steve