Lazy Palms

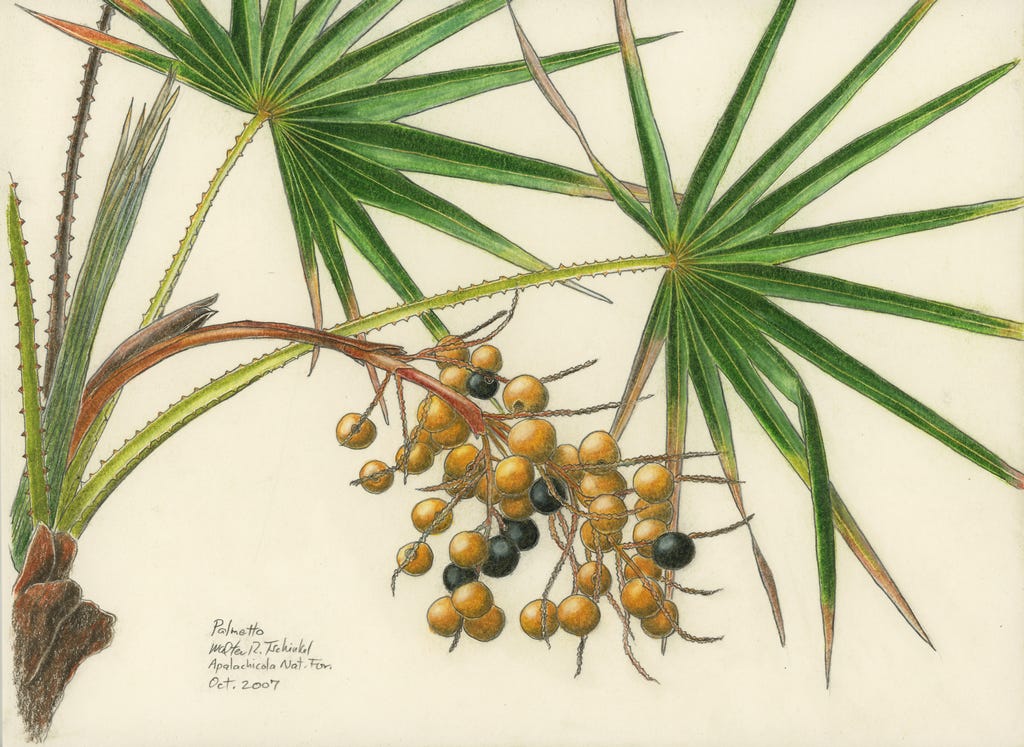

Other than longleaf pine, it is hard to imagine a plant more emblematic of the Florida piney flatwoods than palmetto. Palmetto is, of course, a palm as the name makes clear, but it is a palm with a difference. Where most palms aspire to be tree-like and tall, with a trunk of various sizes and heights, palmetto has given up its fight against gravity and has simply lain down. Botanists refer to its condition as "recumbent", but that is just a fancy way of saying the same thing.

But that is also not the full picture, for what is a trunk in the non-lazy palms is mostly on or under the ground in palmetto and has become a kind of rootlike rhizome. As the new leaves form each year at the end of this rhizome, the palmetto creeps through the landscape at a pace that is not perceptible in the time scale of ordinary mortals. If one could take a time-lapse movie over decades or centuries, it would show the bunches of palmetto fronds zipping here and there through the landscape, like so many bumper cars. Whether they actually ever bump into one another is not clear, for the subterranean trunk gradually rots away at the hind end. If we include that rotting-away, then the palmettos are like a population of caterpillars humping their way through the landscape in random directions. Just picture it….

Land managers usually don't like palmetto because its high abundance suggests too low a prescribed fire frequency. Once the palmetto population is densely established, it takes frequent and hot burns to reduce its abundance. Foresters often resort to big machines to mow, chop and crush it, sort of like mowing a palmetto lawn. It’s an admission that they have been negligent about prescribed burning.

On the other hand, black bears dine on the ample fruits, deer munch the tender, unfolding fronds, and the sprays of white flowers swarm with pollinators. If you get stuck out in the woods without a lunch, but with your trusty machete, you can whack off the growing ends of rhizomes, peel away the surrounding leaves and eat the heart of palm, all pleasant-tasting and crunchy, and a lot cheaper than in a New York restaurant. A small forest-product industry is based on collecting the fruits to make a botanical extract believed to shrink the ballooning prostate gland of old guys like me. Perhaps it works if you believe it.

If you are lucky, you might spot a palmetto tortoise beetle stuck tight to the smooth, waxy palmetto leaf. Thousands of oily, flattened, adhesive hairs on its feet assure that you cannot pull this hemispherical beetle off the leaf (and neither can an ant), but you can slide it off sideways, and when you do and flip it over, the hairy feet make it look like the beetle is wearing boxing gloves.

Adhesion is simply a matter of making contact on a molecular scale, and the beetle is following the simple principle that the more contact, the tighter you stick. When it wants to walk, it only contacts the surface with the tip of the hairs, but when it wants to hold tight, it makes contact with elongated, oily surfaces of the hairs, leaving oily footprints as it goes.

I am reminded of an ad for a brand of glue in which a drop of this fancy glue is put between two flat steel plates, a crane attached to the top plate and a car to the bottom. The crane then lifts the car without the plates coming apart. The irony is that given plates that are flat and smooth enough, you could do the same with a drop of water. The beetle has figured this out. You can confirm it for yourself by pressing two clean microscope slides together and trying to pull them apart again.

Good luck.

Thank you! I love the boxing glove comment.