In 1965, I signed up for an Organization for Tropical Studies (OTS) course in tropical entomology. We ten students and our instructor puttered around Costa Rica in our stubby school bus on roads that were pretty "basic", but we all felt safe because our little bus was driven by Jesus himself who took us from one biologically significant place to another, from high altitude paramos, to tropical dry forest to lowland rain forest. Wherever we went, we devastated the insect population with sweep net, pitfall, black-light, and hand collecting, and spent the nights in front of hissing gas mantle lanterns pinning and labeling our catch and recording it in notebooks. It was classic entomology, and as the number of insect species in these tropical places seemed to have no bounds, most of us were as happy as pigs in poop as insect family names pattered and bounced like rain.

Our example of tropical lowland rain forest was the research station at La Selva. It lay literally at the end of a scary dirt road that clung precariously to mountainsides as it descended to the Caribbean lowlands to a tiny dump of a town called Puerto Viejo, after which we finally crossed a river in a dugout canoe to arrive at the station. We rented an unpainted board shack in Puerto Viejo, a town that had not yet seen its first glass window, and slept in hammocks, or in beds that were difficult to distinguish from hammocks. We set up our equipment and visited La Selva across the river to wander its trails and admire its giant trees and many creeks. The rain forest was but a small piece of an unbroken forest that extended all the way to the Caribbean coast. No doubt, the riverbanks were settled by farmers even then, but we felt like we were at the edge of a real wilderness, and in a sense, we were.

Tiring of rice and beans, we bought an 80-pound raceme of bananas for the equivalent of 1 US dollar from a man in a dugout canoe who couldn't understand why anybody would pay money for bananas, but happily took his windfall. We ate so many bananas that our sweat smelled like bananas. We chased army ants, studied wasps, marveled at termites, collected spectacular beetles, and fell asleep to the nocturnal chorus of howler monkeys and katydids. The magic of unspoiled tropical life settled on us like a gentle mist.

My return in 2004 for an AntCourse was to a world forever and radically changed. La Selva had been acquired by the Organization for Tropical Studies and had grown into a premiere, world-class research station with a suspension bridge across the river, space for up to 100 active scientists at a time, a modern dining hall, dormitories, semi-private rooms, air-conditioned laboratories, a lecture hall, computers, wireless internet, an enormous collection of insects and other creatures, a well-marked trail system, a small shop, and of course, a code of rigid rules of what was allowed and what was forbidden. Wandering the trails, one could still run into herds of peccaries, see and hear monkeys, but one also heard the endless whine of crop duster airplanes spraying the pineapple plantations that now surrounded the 1600-hectare forest island that La Selva had become.

Cooling off under a small waterfall, or swimming in the river was still fun and pleasant, but the wilderness spirit had completely vanished. The town of Puerto Viejo had glass windows, the road was paved and extended to the coast and we no longer slept on hammock-like beds, and instead of working to hissing gas mantle lanterns, we watched slick presentations on PowerPoint, and the price of bananas was no longer a dollar for 80 pounds.

first, that great picture of you and the others - -what of course, struck me is - not a single woman! what's the percent now in entomology?

second-- what a wonderful description of being hands-on in the forest of that time! (I trust you had good shoes, you must have been barefoot only for moments - I have found in my 11 brief visits in Ecuador's rain forests, from 1981-2018-- that feet were always at risk of various forms of ants.) And the endless forests everywhere! Now, as you cruise down the rivers to the still-anxiety-producing airports, there is just a decorative band of vegetation along the banks, but behind that strip? oil extraction, destroyed forests, no sense of the people who used to live there. No news I can bring here, it's well known and criminal.

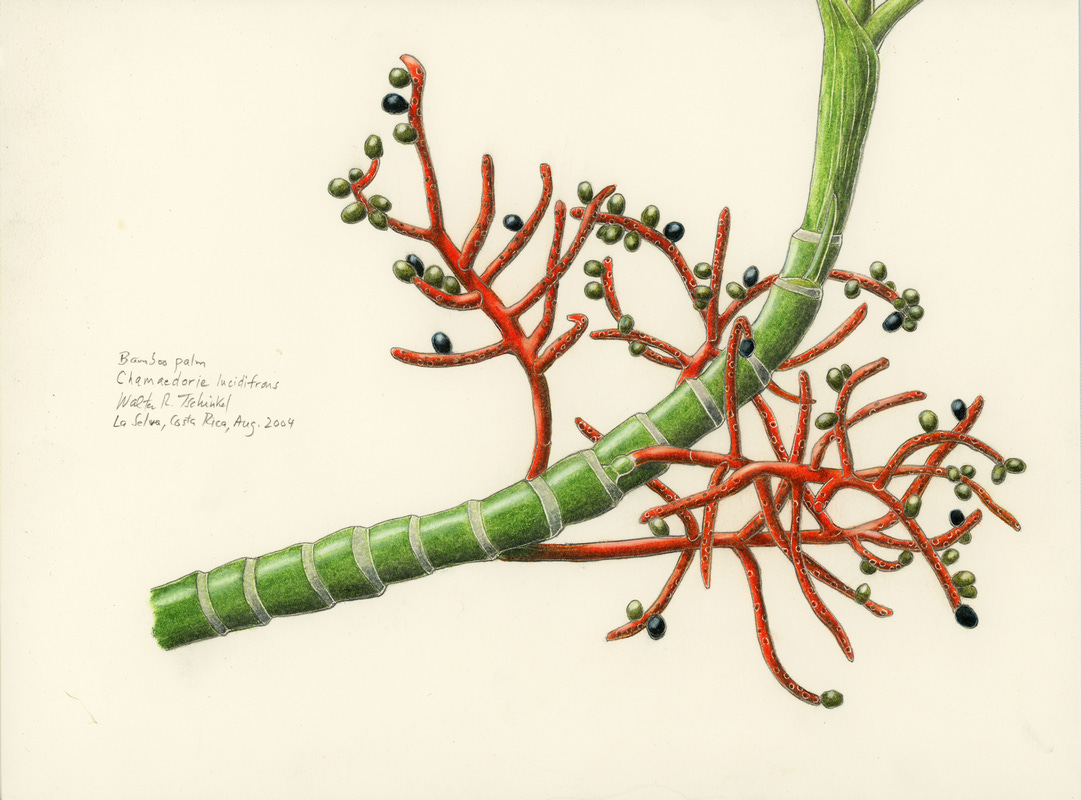

Thanks for this account, Walter, and the strikingly beautiful images (is it "paintings" or "drawings"?)

This reminds me of a tropical ecology course I took in Belize seven years ago. We were still able to explore the varied tropical habitats and sleep in our hammocks, guided by a brave bus driver across bumpy dirt roads. I'm sure I'll look back on those days for many more years to come, just as you look back on La Selva.