It is never balmy or warm in August in the Uinta Mountains above 10,000 feet elevation, but when Dennis and I made a two-week backpacking trip there, even the days drained us of whatever heat our struggling metabolisms were able to generate. During many of the sunny days, we wore our down parkas much of the day even while hiking, and during some of the nights, it was so cold, and our sleeping bags so inadequate that even with all our clothes on, we slept between two fires. As the fires died down and the cold overcame us in our sleeping bags, the first one to wake would stoke the fires again. In the mornings, any water in a pot was frozen solid, and frost crystals inches tall pushed up from the damp ground.

Setting aside Dennis’s altitude sickness on our second day, there was a dream-like moment when I saw the crown of a very tall black hat rising over the brink of the downhill view, followed by a Ute Indian on horseback. Was I in a western movie? He was a shepherd coming to check on his sheep. There was a shepherd’s cabin over rise, he told us. After he rode off, I tried to start a fire, and then it was I who had the sickening feeling when I realized that all those Strike-Anywhere matches that had been kept in the attic of our house in Tallahassee, the Humidity Capital of the Western Hemisphere, had become Strike-Nowhere matches, and we had two weeks of hike and many fires to go. I took off on a desperate run to catch up with the shepherd, and when I caught up, wheezing with the altitude, I gasped, “Our matches don’t work. Do you have any matches to spare? “Sure,” he said, “I got a book of matches you can have.” I have never considered a book of cheap paper matches with a picture of a scantily clad woman and inscribed “Kitty Kat Klub” as precious as that one. In the next two weeks, any fire that took more than one match to start was followed by panic.

The Uinta Mountains were glorious, with glacier-gouged lakes and wet meadow basins alternating with flat-topped ridges and peaks, for the Uintas are not mountains in the usual sense, but glaciated plateaus of level sedimentary rocks rising to over 13,000 feet. The peaks beckoned, and Dennis and I huffed and puffed up one of the highest ones, proud of our conquest. On the few “warmer” days, we took quick baths in the icy lakes and Dennis fished for trout to improve our boring hiker’s diet. With the same goal, I collected piles and piles of Suilus mushrooms, so many that Dennis paled every time I brought in more.

A hike that long requires packing two weeks of food, and variety and appeal become victims. Sweets are a major challenge, so we packed in pudding mixes that could be cooked quickly. Most nights, we built fires backed by one of the many flat rocks of the region, rocks that reflected some of the precious heat back on us, while simultaneously heating our food faster. On the night in question, this was going very well, and I stirred the instant pudding mix enthusiastically, anticipating something deliciously sweet to come.

Suddenly, there was a huge bang, and I was hurled backward onto my butt. It took some seconds for me to gather myself, and when I did, I saw splatters of pudding on my clothes, on the ground around the fire, and on the rocks of the fireplace. I saw immediately that I had been the victim of an Exploding Pudding. The force of this explosion had been sufficient to split the flat rock behind the fireplace, and to spall off a layer of it, scattering rock fragments for a couple of feet around. A narrow escape.

I had not yet burned the empty pudding box, so I wrote down the brand and vowed never to buy it again. And I haven’t.

I know what you’re thinking. Puddings simply don’t explode in this world. However, my experience of being hurled backwards by the force of the explosion, and subsequently discovering that the explosion had not only blown pudding over a large area but had shattered a rock as well was strong evidence. That is not a pudding to carry on a long backpacking trip, no sir!

As for the point you are about to make about correlation and causation, hey! I’m a scientist and distinguishing causation from correlation has been my career. And I’m telling you, that big bang and the pudding shower came before I saw the rock in fragments.

We decided to play it safe and didn’t cook anymore pudding on the rest of this hike, and just to prove my point, we didn’t have anymore explosions either.

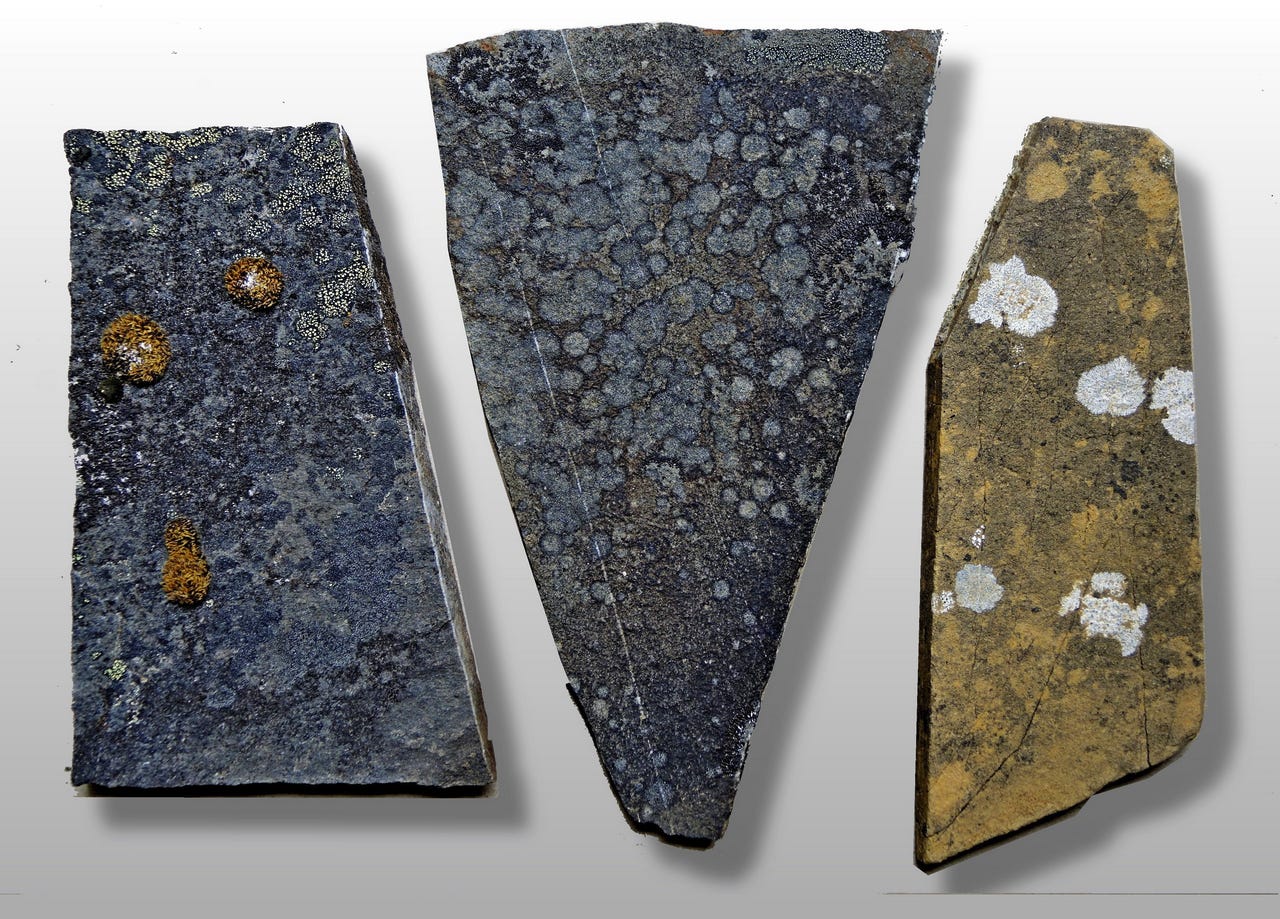

As we made our way down the trail back to the car after two weeks, we passed through an area in which the flat shale rocks were separating into layers, with artful lichens decorating all the exposed surfaces. Our packs were a lot lighter because we had eaten two weeks’ worth of food, and so as not to float off into the air, I filled my pack with a few beautiful rock-and-lichen specimens. These are my belated Found Objects for this essay.

Finally, here is my recommendation: think carefully before cooking instant pudding.

Exploding rocks often have trapped moisture inside. Very dangerous indeed

Ok, I can hazard a guess, the Uintahs are composed in part by micaceous shales. If you had your fire above an oil bearing micaceous shale you might see an explosion? Maybe????