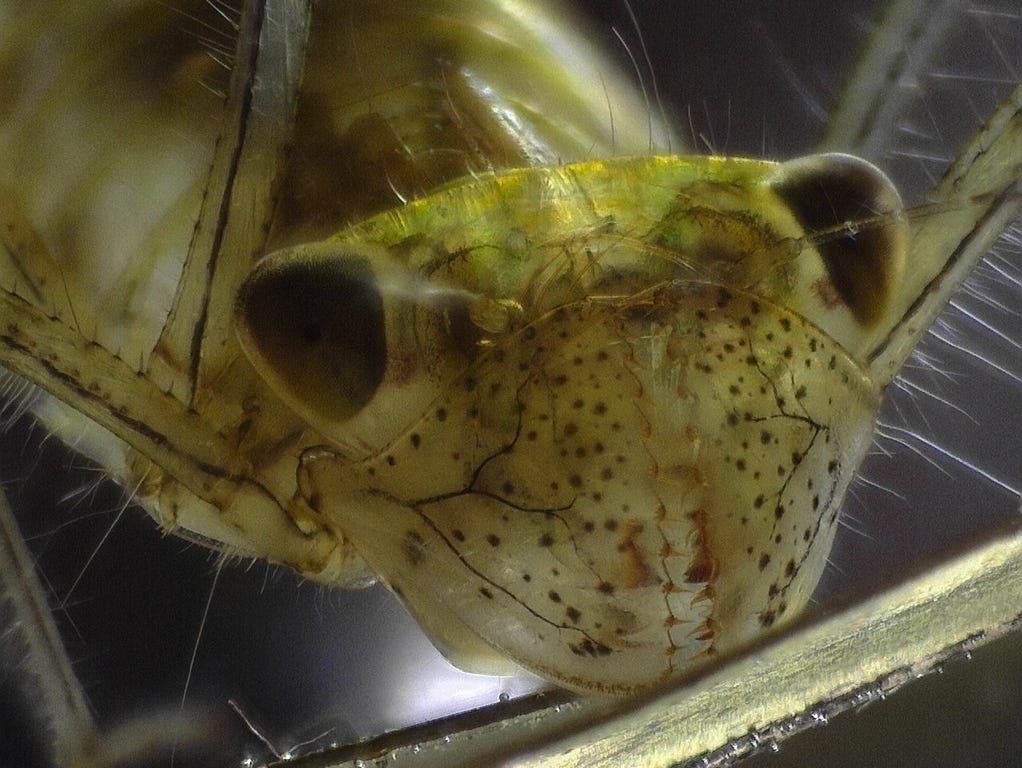

Many years ago, I discovered the lovely transparent nymphs (immatures) of dragonflies in temporary ponds south of Tallahassee. What made them charming was that, without dissection, you can easily see all their internal parts at work— the pumping gill, the pulsating heart, the circulating blood, the twitching muscles, nervous system, digestive system, and air-filled tracheal system. These aquatic nymphs hide no secrets from prying eyes. I have written about several of the internal systems of these beautiful creatures, but here I want to describe an external feature, specifically, how the mouthparts of this voracious predator have evolved into a lightning fast, raptorial apparatus for grabbing prey. Like the praying mantis, these are lie-in-wait predators, calm and still until an unfortunate prey animal wanders across their visual field. Like the mantis, they have large, motion-sensitive eyes that feed input to optic lobes and the brain, but unlike the mantis, everything inside their head is visible through the transparent head capsule, as below.

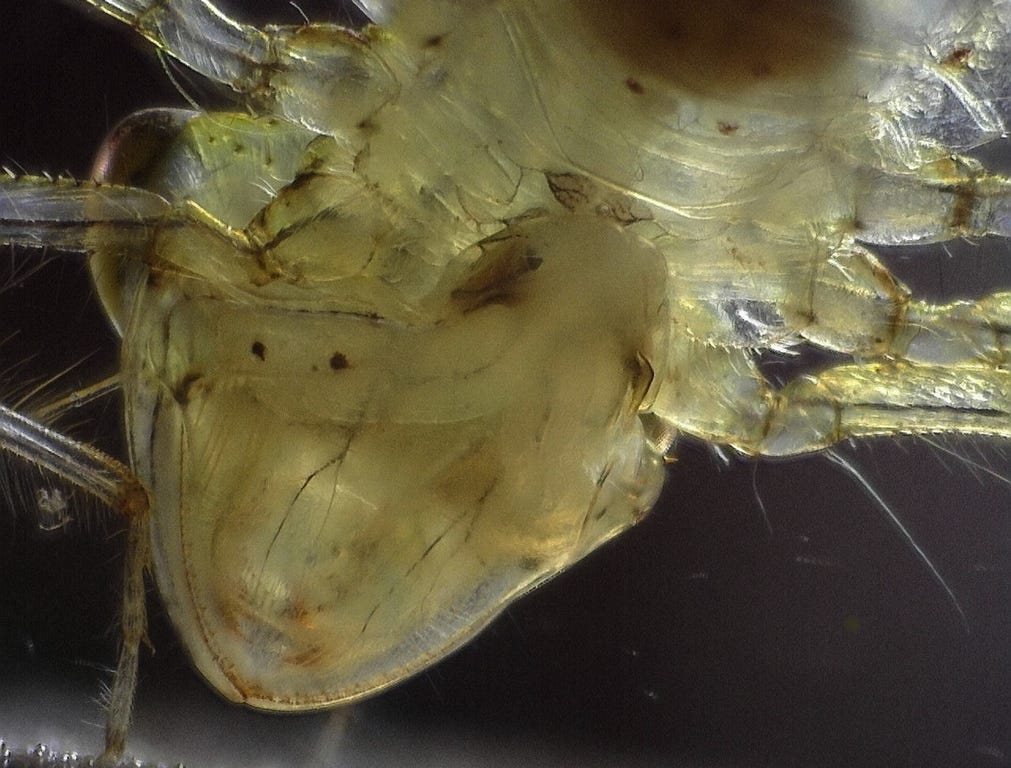

So, if you were a mosquito larva, this would be the last thing you saw—

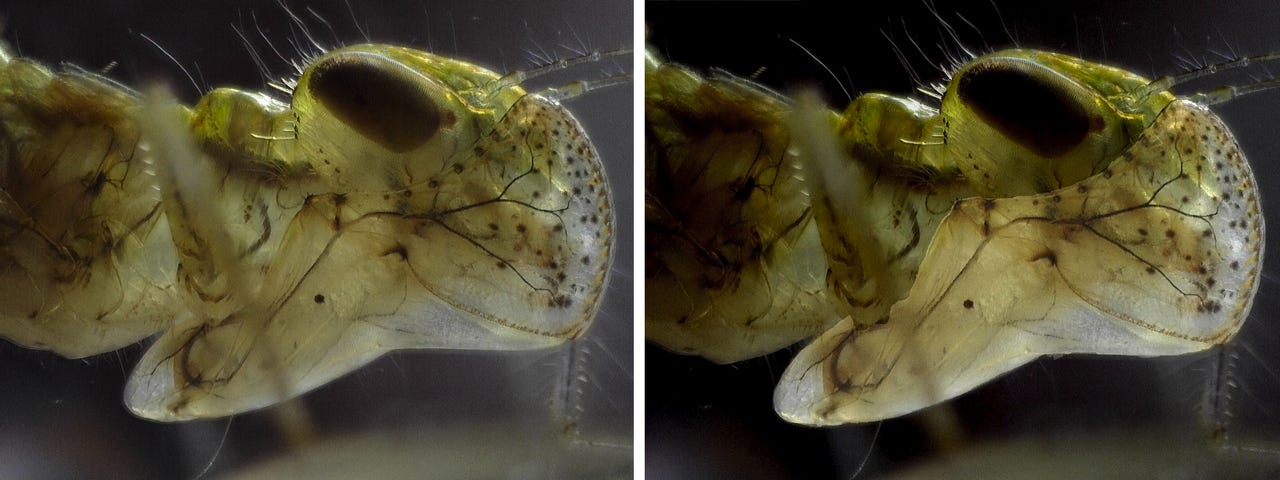

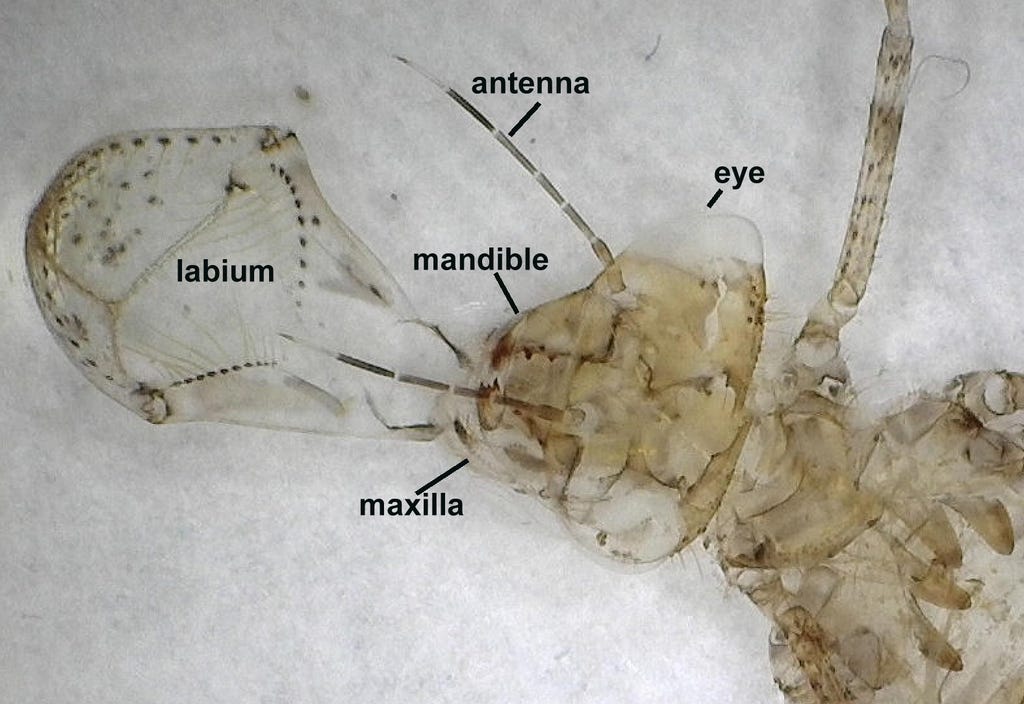

The large, mask-like structure covering the nymph’s face is the big, scoop-like, business end of the third pair of mouthparts, the labium. You can see the toothy mandibles and the spiky maxillae through it. This labial mask can be extended in a flash toward a hapless prey animal. The mask opens into a catch-basket to capture the prey, which is then brought to the face to be chewed up and macerated by the maxillae and mandibles.

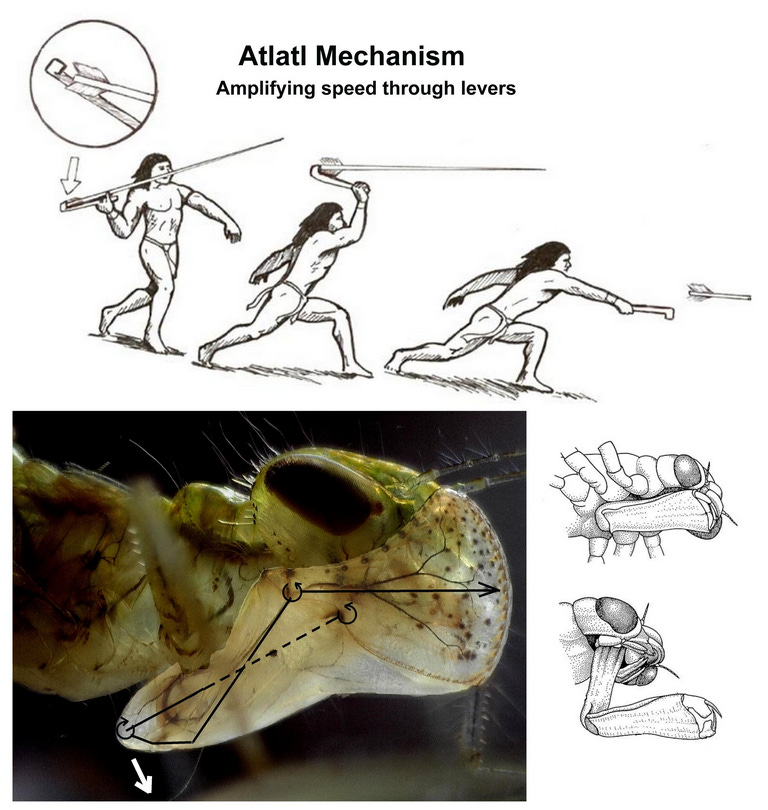

Seen from the side, the whole labial mask extends backwards as far as the second pair of legs. At the hindmost extent, there is an elbow-like joint that can be rotated downward and forward, while simultaneously opening the scoop. The elbow joint is clearly seen in ventral view below. Note that the joint is provided with large muscles to allow rapid extension of the apparatus.

Dragonfly nymphs, like all insect, grow by molting, shedding the old exoskeleton for a new one formed inside the old. All external structures are present in the molt, including the labial mask. In the molt, it is extended rather than held covering the face, thus revealing its structure.

Given its structure, especially apparent in side view, the labial apparatus has a mechanical resemblance to a spear-throwing stick, or atlatl. The atlatl acts as a lever that transfers the force the thrower exerts on the end of the lever into the speed of the spear. In a similar way, the extension of the first segment of the apparatus is like the movement of the atlatl, transforming force into the speed of extension through the elbow.

You can see the apparatus in action in the video below.

Even though changing forms and functions is the bread and butter of organic evolution, there is still something wonderful and illuminating about comparing the starting material with the end product. For our nymph’s labial mask, the starting material is something like a generalized insect labium, the hindmost of the three mouthparts. It is itself divided into several segments, each with (I presume) a different initial function. Extreme changes in the shape of the several pieces lead to the labial mask of dragonfly nymphs, as color coded below.

Any student of insects could fairly point out that this is far from the most extreme modification of insect mouthparts. Major insect groups are defined by how the mouthparts are modified for piercing/sucking, sponging, sipping, stabbing/lapping, manipulating, and so on. In many cases, the mouthparts are changed beyond recognition, and would be worth some future essays. But I must confess that my transparent dragonfly nymph has stolen my heart because it keeps no secrets from me, and rewards me with new marvels every time I put it under the microscope.

And they look so sweet...

I loved this essay; and it takes me back to my wonderful high school biology teacher who inspired my attraction to the living, evolving animal kingdom.