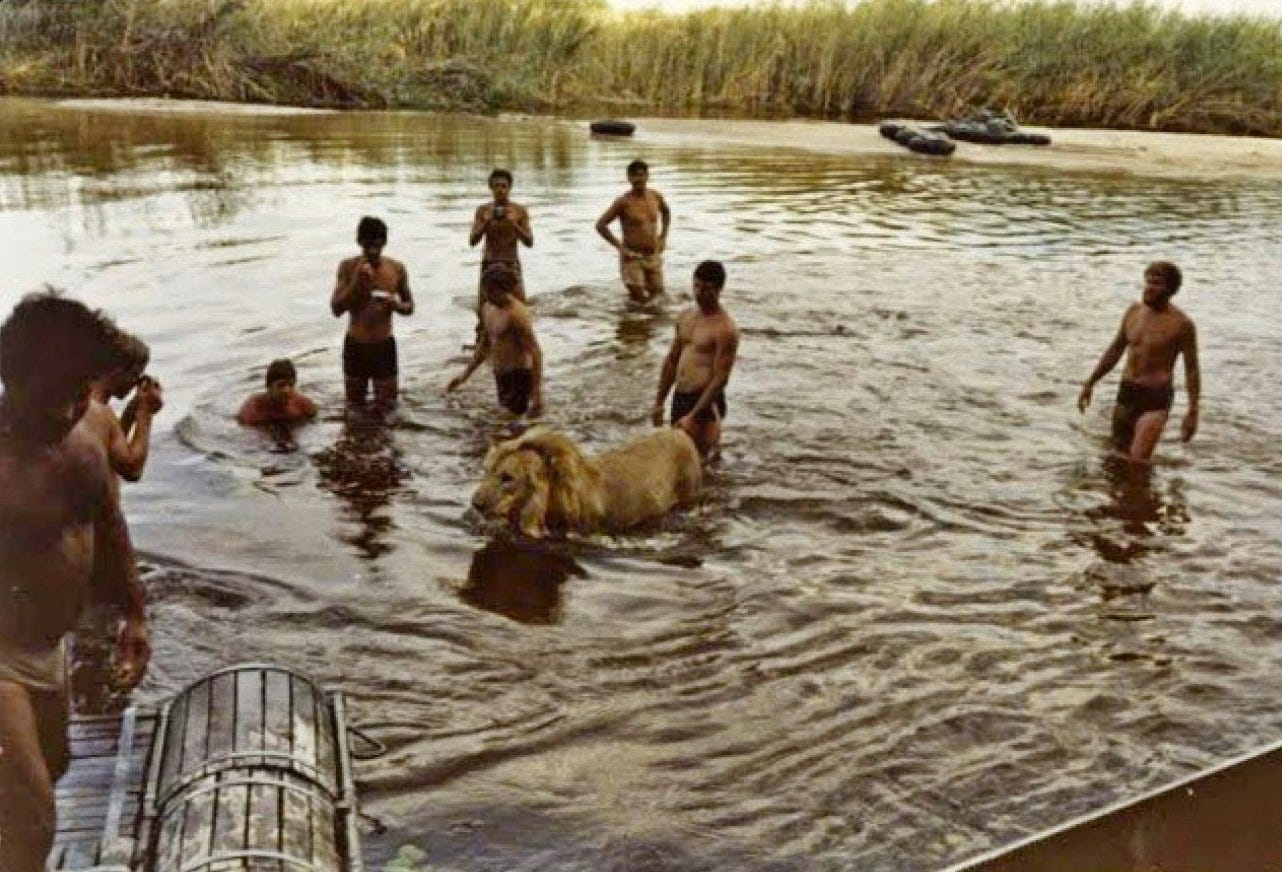

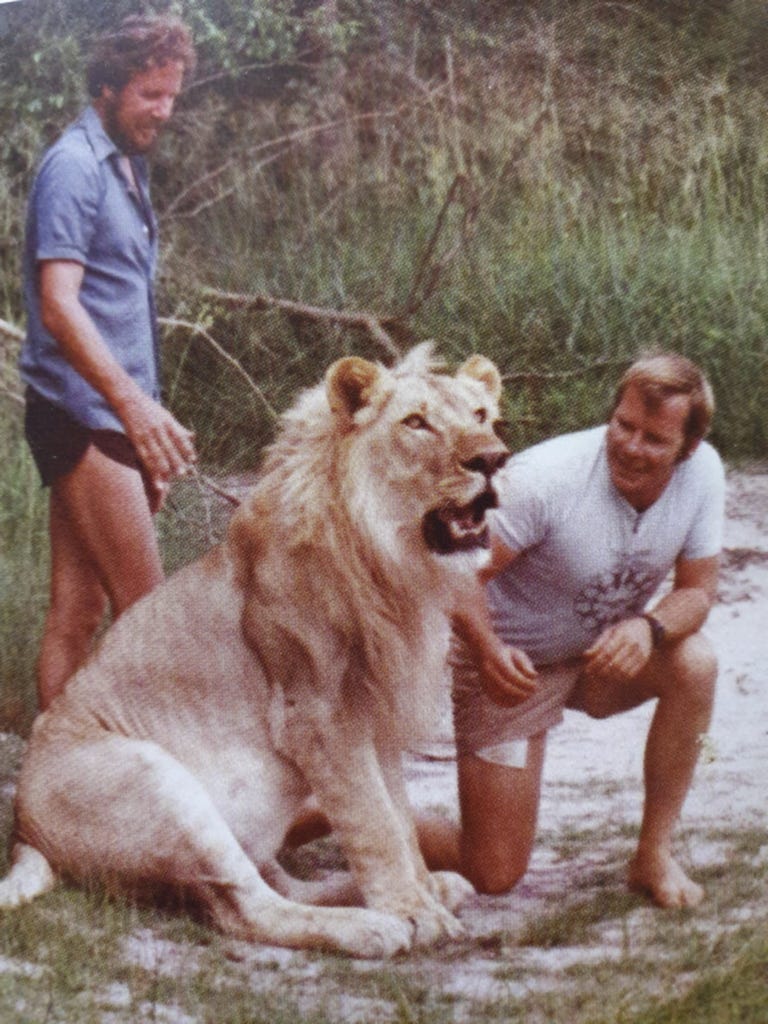

In the Angolan War, the Caprivi Strip was a remote frontier where young South Africans trained for the bush war raging north of the border and fought alongside die-hard colonels resisting the tide of history in that complex conflagration. The lumpy track from the airstrip to Nambwe Safari Camp winds through a forest of Zambian teak whose profuse blooming distracts one from a few concrete pylons, empty brick foundations, steps to nowhere, a small monument without a plaque and a hilltop observation platform overlooking the green meanders of the Kwando River floodplain. This was once Fort Doppies, a remote military outpost on a hill where soldiers trained in bush war tactics, tracking, and survival skills. The name was coined by recruits who observed a vervet monkey that would sneak in to steal spent cartridges (called doppies in Afrikaans). In time, the camp adopted a male lion cub, Terry (or Teddy by some accounts). After he grew into an adult, he alternated roaming the bush with visiting the camp to socialize with the soldiers. Pictures show him swimming with soldiers, getting out of a helicopter and generally acting like one of the boys. Most disconcerting, he would sometimes come into the huts in the middle of the night, plunk his full weight on top of a soldier and fall asleep as the soldier screamed for help.

Fort Doppies was abandoned in 1990 when Namibia gained independence, and the area is now prime safari country with camps and lodges where the well-heeled and adventurous hope for face-to-face encounters with lions and hippos, or perhaps, with luck, get a glimpse of a leopard. Were Terry the Lion to wish to share their nocturnal bed, they might die of fright.

Soldiers no longer scan the Kwando flood plain for insurgents, and no longer receive tracking instructions from diminutive Sani bushmen wearing army uniforms specially made to their size. But the forest of Zambian teak still flowers profusely every summer, offering millions of flowers to pollinators in hopes of producing a handful of seed pods that, when ripe, explode to scatter the seeds. All this so that in a century or two of its life, the average tree, with luck, will produce one survivor, its own replacement.

Back when it was still called Rhodesian teak, these trees were hewn into millions of railroad ties that brought rail travel to much of southern Africa. It is a beautiful, dark wood, so hard and rot resistant that after a century in the ground in the company of termites, the old ties now sell for much more than they did when fresh. Working the wood can be trying, for it dulls blades fast, and the sawdust is irritating to the nose, but the effort and aggravation are rewarded with a dark, glowing polish even without varnish.

I sometimes wonder if the soldiers at Fort Doppies knew the beauty of this wood or knew that it undergirded southern African railroads. Their remote military posting suggested a familiarity with the outdoors, perhaps by way of farming or even wilderness, perhaps by way of hunting, for how else could they have been expected to be useful in this bush war. But I like to think that when the trees were in full and fragrant bloom as we saw them, some of the soldiers momentarily forgot why they were there, and simply delighted in the spectacle of an entire woodland flowering at once.

A fascinating reminiscence. Your telling transports the reader back to the place and its curious history.

interesting how the vocabularies of groups, causes, interests evolve over time. you do the terminology dance very well. and great descriptions - did you manage to take a little of the teak home with you for making a tiny sylvan work of art?