Vertebrate skulls make good Found Objects, and I have collected a lot of them. Most of them are mammals or birds, including armadillo, bobcat, dog, cat, fox, sloth, gannet, pelican, caiman, kangaroo, and porpoise. The porpoise skeleton I found on the beach in the 1970s has rewarded me with several stories because compared to “ordinary” mammalian skeletons, the porpoise’s is bizarre. I wrote an essay on the porpoise’s neck and showed that its extreme shape was the result of evolution tinkering with the relative growth of the neck vertebrae.

Here I want to pick up the relative growth theme in greater depth with the much more complex story of how the component bones of the mammalian skull get morphed during evolution to change the overall shape of the skull, and how extreme such shape changes can be. By “shape” I mean a set of proportions that describe an object independent of its size. For example, the earth is much bigger than a billiard ball (yes, really!), but the shape of the earth is the same as the shape of a billiard ball, at least within the limits of measurement (OK, I know the earth is not a perfect sphere, but then neither is a billiard ball). The mammal skull arose through the gradual addition of bones derived from skin and cartilage during early vertebrate evolution, and by the time mammals descended from reptiles, the skull bones had been pretty much standardized, and all mammalian skulls were composed of the same homologous bones (homologs are structures that descended from a common ancestral structure). Looking at the dog and porpoise skulls below, you might not immediately think that every skull bone of the dog corresponds to one of the porpoise’s, but I will show that this is true.

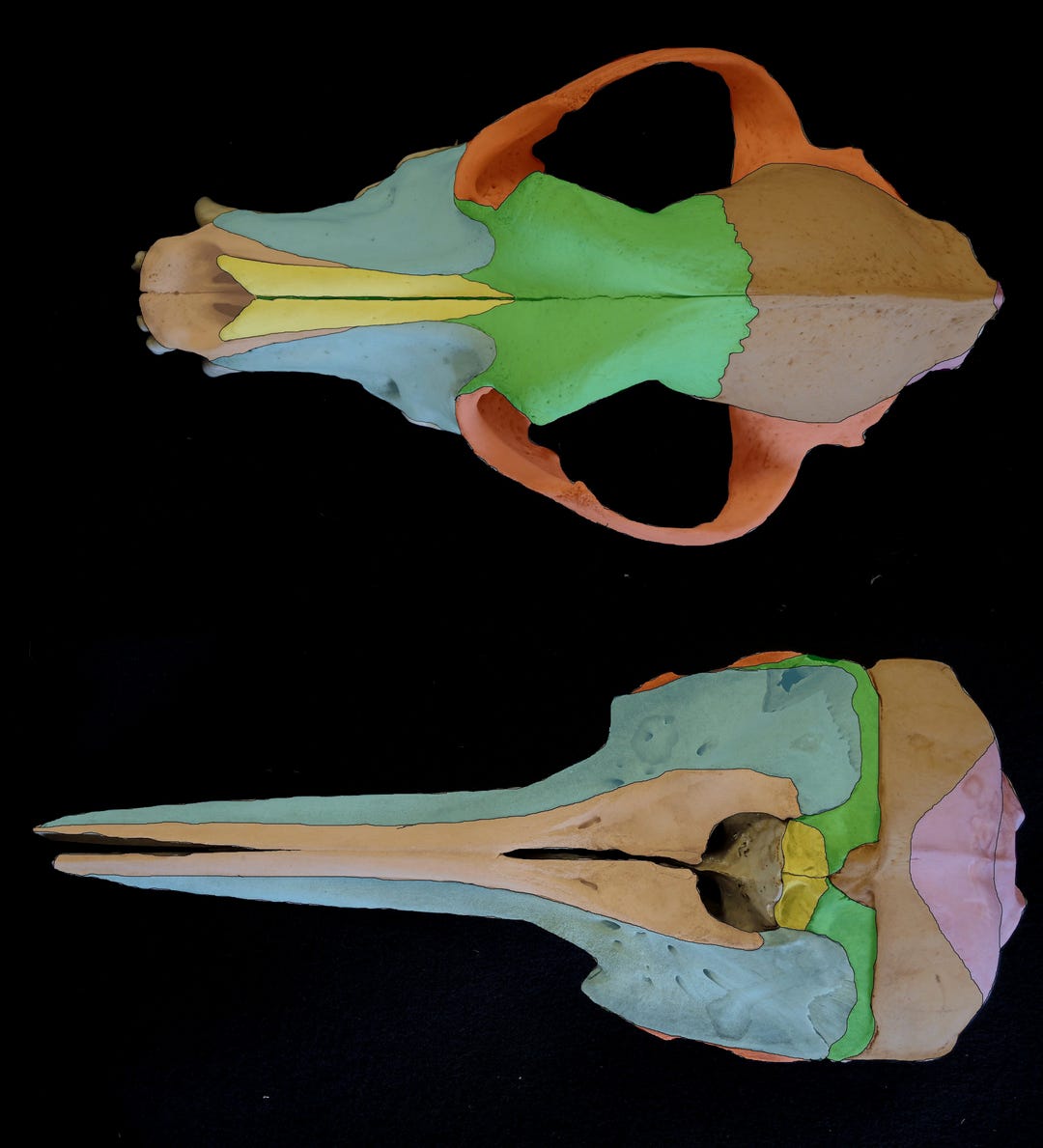

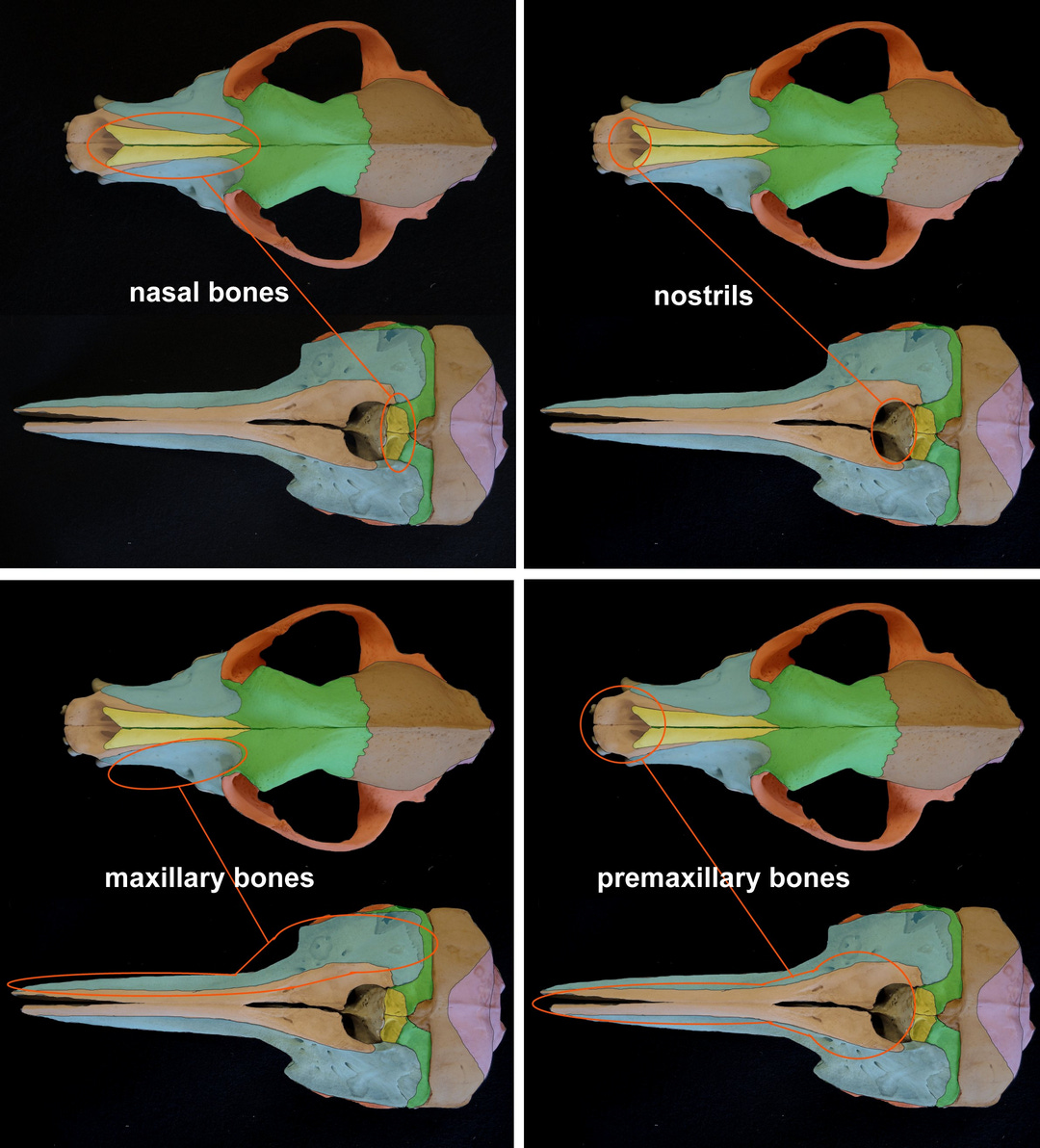

I will start with the hound dog skull, not because it represents an ancestor to the porpoise (it doesn’t), but because the major skull bones can be easily identified and seen, and not least because it is one of the Found Objects I collected in the piney woods after the end of a hunting season many years ago (you don’t want to know why the dog died). For visual ease, I color-coded the homologous bones in both skulls and show them as seen from above. There are a lot more bones in the skull, but they are not visible in this view, and are not needed for my story.

Compared to the dog, the porpoise has a long, pointy snout, a beak almost, and a large, round braincase, and the whole skull seems to have been drawn out forward and compressed from the back. In a sense, this is exactly how the differences between dog and porpoise arose, not through pulling and pushing, but through relative growth of those parts.

Three bones--- the nasal, the premaxillary and the maxillary--- make up the front of both skulls. Compared to those of the dog, the premaxillary (beige) and maxillary (blue) bones of the porpoise are huge and elongated while the nasal bones (yellow) are shrunk to a lumpy remnant. Because the nostrils are the space between the nasals and the premaxillaries, the nostrils of the porpoise are now on top of its head (the “blow-hole”), a clear adaptation to living in the sea and having to breathe at the surface now and then without sticking your head up out of the water. I suppose porpoises could have evolved a snorkel, but how would they have done that?

The maxillary bones bear the teeth in both dog and porpoise (and us, for that matter), and the greatly elongated maxillary in the porpoise forms the business part of the porpoise’s beak with its row of undifferentiated teeth (lost in my specimen).

These changes are accompanied by equally large changes in the back part of the porpoise skull (the braincase) --- the frontals (green), parietals (brown) and occipitals (violet). In the porpoise, frontals are thin strips squashed against the parietals, which in turn are encroached upon from the rear by the occipitals (which are barely visible in a vertical view of the dog). Finally, the bony zygomatic arches (red) that accommodate the eyes and jaw muscles of the dog are greatly reduced, and located on the side of the head, barely visible from above. The surfaces to which the jaw muscles attach have moved rearward and downward in the porpoise, relative to the dog.

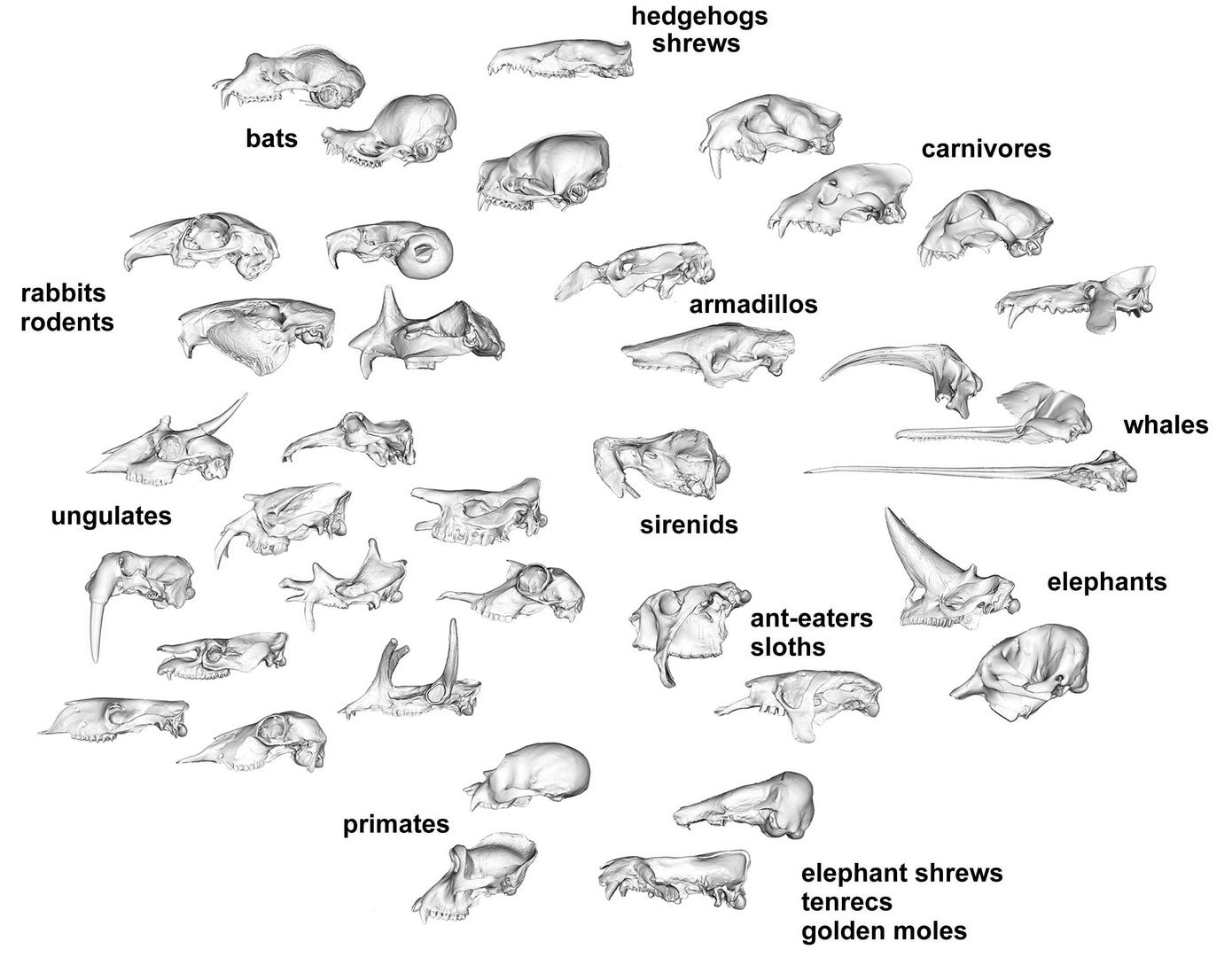

All changes of shape evolve through changes in relative growth of the parts, dramatically illustrated in my dog-porpoise example. Extending this understanding to the amazing diversity of mammalian skulls shows the capacity and flexibility of this process. A few examples of this diversity are shown below, taken from an article on the rates of skull evolution in placental mammals (Goswami et al. Science 378 (6618): 377-383 (2022)). All these skulls are built from the same set of homologous bones, and their many eye-popping projections, distortions, reductions, accentuations, and exaggerations, even the wildly divergent skulls of whales, are all the products of this “simple” process. And of course, all these shapes are associated with biological functions, be they feeding, defense, display, competition, sensation, and many other things that mammals do. Changes in shape accompany changes in function.

The fact that evolution always acts on something that is already present is a fundamental constraint on what can and cannot evolve. Life is not planned by engineers--- it does not evolve through the invention of something new, or some novel process in response to some perceived need. That is why the porpoise does not have a snorkel. No, life evolves though endless tweaking, nudging, reducing, losing, amplifying, and minor modifying of the material already at hand. That is the fundamental difference between human invention and biological evolution, and is why so many of the things that living creatures do seem to make little sense to an engineer or inventor, and often appear to be nutty and strange. Life is the result of four billion years of workarounds and trial and error on an enormous and ever-shifting pile of chance variations. The path leading from a common ancestor to the dog and the porpoise is defined by stark differences in relative growth of the ancestral parts. While it may be true that you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear, you can make an elephant’s or dog’s and a lot in between.