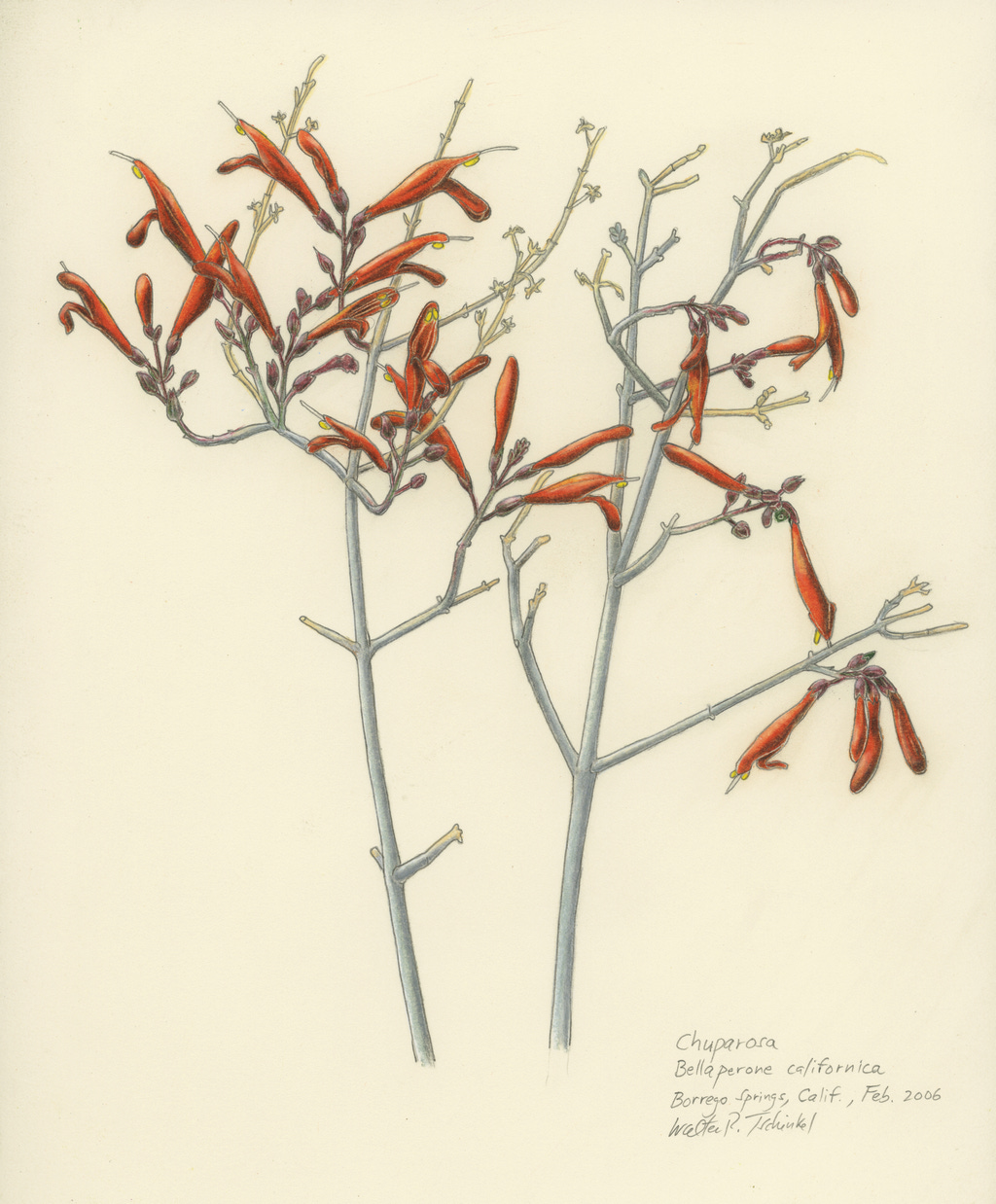

When a flower offers nectar to an insect, it expects pollination service in return, a sort of goods for service arrangement. Much of the time, this works out reasonably well, with insects busily contaminating the flower's stigma with pollen. In many cases, flowers are not aiming to get pollinated by just any old insect off the street, and limit access to the flower by evolving various contrivances both to attract the desired pollinator, and to exclude the undesired. The two big filters are flower color and flower shape. Because insects don't see red, red flowers are usually evolved to attract vertebrates such as birds, which can. When the flower is a long tube in addition, with the nectar glands at the bottom of the tube, as for example in chuparosa (Justicia californica) in the Anza-Borrego Desert, the desired pollinator is often a bird with a long beak, e.g. a hummingbird.

As the hummingbird dips its beak deep into the flower to reach the nectar at the bottom, its head is dusted with pollen from the protruding anthers, and because the bird moves from flower to flower of the same species, that pollen will adhere to the even more protruding stigma of the next flower. In this way, the bird obligingly pollinates one flower after the other. As payment, the bird gets a sip of nectar from the glands at the bottom of each tube. Hummingbirds in the Anza-Borrego Desert are so fond of the flowers of chuparosa that each bird claims and defends its ownership of particular bushes. Bushes can be so large that the effort and confrontations of defending them pays off handsomely in nectar even to the most nectar addicted bird. The large bush is necessary because only the terminal two or three flowers on a branch secrete nectar, and only for a day at that, so by mid-morning, most of the flowers have been sucked dry. You snooze, you lose.

But somehow, honeybees and native bees are also attracted to the flowers, even though they are not supposed to be able to see red. No matter. They arrive in numbers, but there is no way they can either squeeze their way down the tubular flower to the nectar or to reach it with a long tongue. The flower has seen to that.

So, the bees do the only other possible thing--- they turn to crime and robbery. Sitting on the back porch on any spring morning, I don't have to watch very long before I see a bee chewing through the base of a flower to get to the nectar inside. The bees are nowhere near the stamens and thus do not perform the service for which the nectar is the intended payment, so this is robbery. Crime seems to pay, or maybe the sheriff is looking the other way, for the frequency of holes in the flowers reveals that such robbing is not rare. And as in any case of robbery, the act deprives not only the flower that made the investment, but also the legitimate pollinator, the hummingbird that depends on the nectar. It seems like an open and shut case--- bee burglars are stealing from both the flowers and the hummingbirds.

Oddly, the jury is still somewhat out on this case. With typical biological complexity, it is likely that hummingbirds, being sharp of eye, can tell if a flower has been robbed, and avoid that flower, but move on to others. The bird must thus fly farther, an energetic cost, but the flower may benefit from increased out-crossing. The plant may not be as passive as it seems and may allocate more resources to unrobbed flowers or may time nectar production to avoid peak robbing activity. Even high rates of robbing have been shown to have little effect on seed production. The exposure of the nectar source in the bottom of the robbed flowers may attract secondary robbers (honest, officer, the door was open!), some of whom are also part-time pollinators, complicating the math of cost/benefit to several parties. The jury will surely be mulling this over for some time to come.

Biologists like to use terms defined in human societies, many freighted with moral judgements, and to apply them to phenomena in the living world. I suppose the intent is to increase understanding, and indeed, they often offer helpful parallels. So, we get terms like “robbery”, but even in human society, “robbery” is not a simple phenomenon, and societies put a great deal of thought into laws and moral standards that define what “robbery” is and isn’t. Applying moral standards to the living world is likely to reduce understanding, rather than provide clarity. It might be much better to reverse the logical flow by seeing human morality in the light of a deep understanding of biology. What might the biological underpinnings of moral systems be?

An Addendum

Very occasionally, chuparosa flowers are yellow rather than red. Most likely, the plant does not make the red pigment, thus exposing the yellow pigment that is normally not visible in the company of the red. It is also possible that the yellow pigment is a modified version of the red that makes it absorb shorter wavelength of light. In the context of attracting pollinators, if birds really do cue to the red color of chuparosa, do yellow chuparosa flowers get fewer visits from hummingbirds? Do they get more visit from bees and other insects? Are they more or less likely to be the victims of bee crime? Another project for the next visit to Borrego Springs.

Late to the party. My apologies and also appreciation of this essay and also the comments which always constitute a welcome annotation.

Moving from bees and birds to ants! Walter did you get wind of the Aussie's losing war against fire ants?

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/mar/04/australian-program-to-eradicate-red-fire-ants-is-a-shambles-senate-inquiry-told/

You should have been called in as an expert advisor!

i know you didn't- i'm a careful reader. it's just that the very variation of circumstances you describe made me think of that wider context. love the messages and paintings in any case!