The steep mountainside behind Cliff and Peggy's house in Hermanus, South Africa is covered in fynbos, a shrubby vegetation adapted to extremely poor soils and frequent fires, cold rainy winters and hot dry summers. Add to that extremely nutrient-poor, sandy soils weathered from sandstone that was formed from already nutrient-poor sand. As this has been going on for millions of years in these scattered valleys and mountains, the species diversity is astounding. You can stand on a line where two soil types meet, and more than half of the species on the two sides will be different. The area of this Cape Floral Kingdom is the tiniest of the six floral kingdoms, dwarfed by a factor of thousands by the largest. Of its 9,000 plant species, almost 70% are endemic, as are 12 plant families. The variety of flowering plants is simply breathtaking.

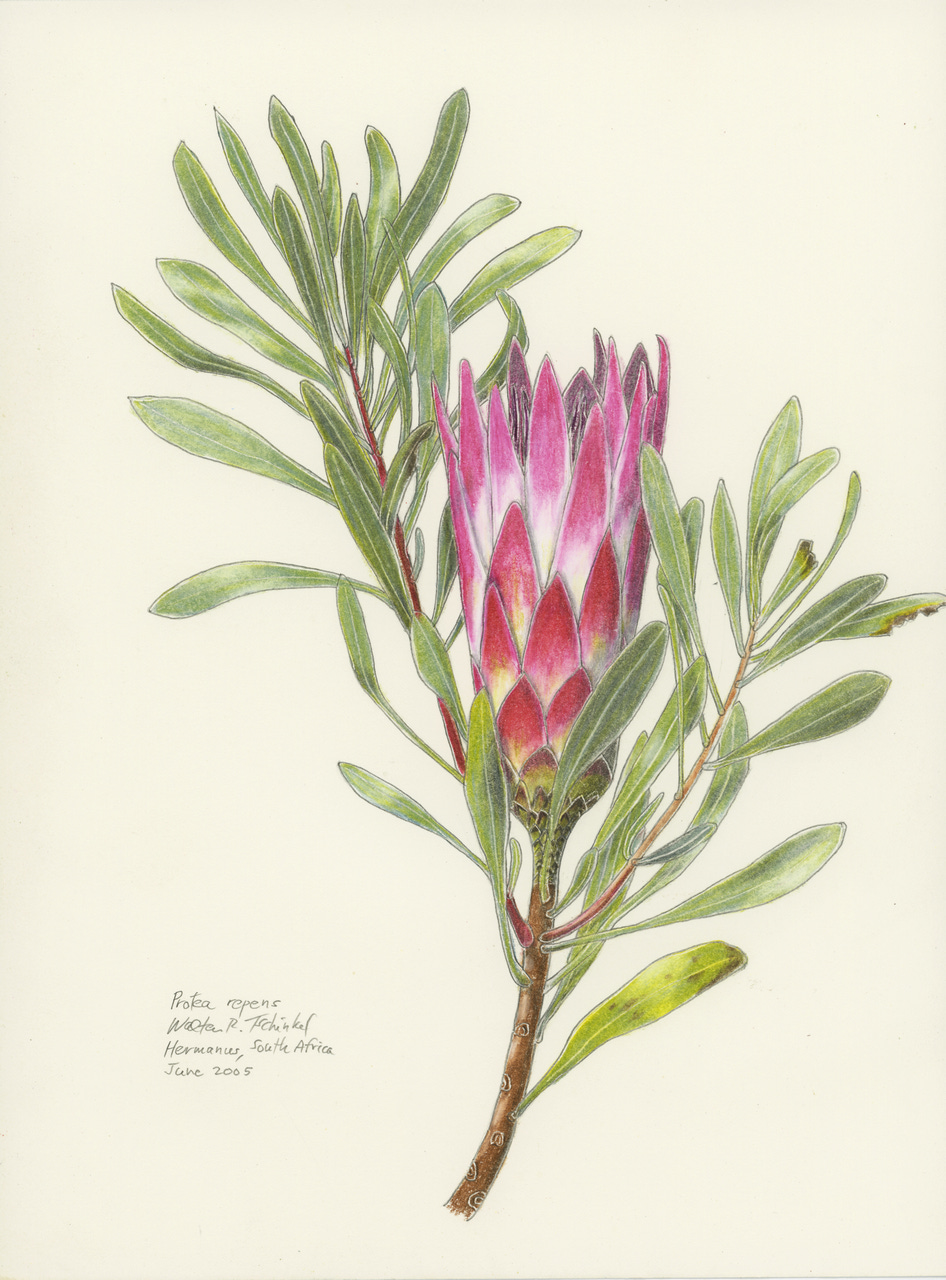

Among the most interesting is the endemic protea family, some of whose species have entered the world floral trade, for many have huge, long-lasting, beautiful flowers, including the King Protea, the national flower of South Africa. Nowadays, you can order a bouquet of proteas almost anywhere in the world, and punch it up even more with several other fynbos endemics now available in the floral trade.

So, for me, no visit to South Africa is complete without a ramble through the fynbos, and the mountain trail behind Cliff and Peggy's house allows me to do just that. This time I am lucky as Protea repens is in bloom (see my drawing above). I am not the first to discover these flower heads with their walls of surrounding pink bracts around the densely packed disc of florets--- a couple of sunbirds and a sugarbird are busy dipping their beaks deep into each floret to sip the nectar, powdering their faces with pollen, thereby paying for the nectar with pollination service. The birds dip and sip, and I think it has to take a mighty large flower to keep these birds in sugar. These pollinators are no bees weighing mere milligrams, but birds in the multiple gram range, a thousand times as heavy and necessitating a thousand times as much food.

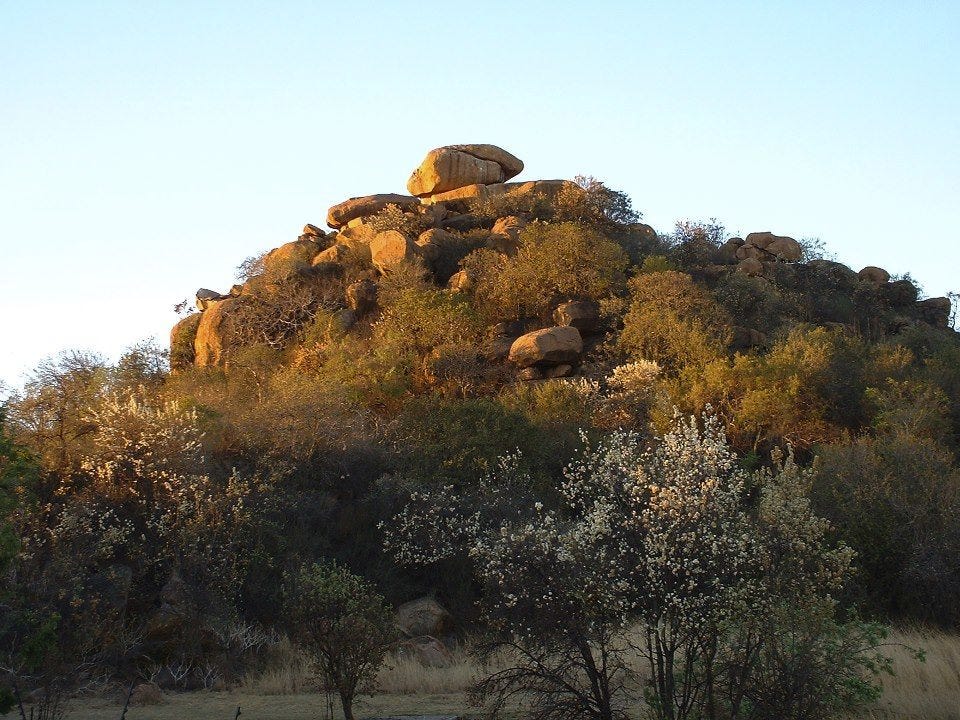

From the cliffs above the trail, I hear barking. On a rock outcrop sits a troupe of baboons, and the trail passes within a few meters of them. Statistically speaking, baboons are not injurious to humans, but seeing those huge, razor-sharp canines makes one unwilling to take a chance, as does any experience with their guile and intelligence. Keeping an eye on this group as I pass, I remember the famous "baboon incident" in Kruger National Park back in 1970.

Back then, as we watched a troupe of baboons near a koppie (a rocky outcrop), a young male leapt onto our hood (aka bonnet in South Africa). Very cute, we thought, until he spotted the apples on the back seat and began to demand one by wrenching at the windshield wipers and rear-view mirror, as though he knew the car was a rental, and we were liable for damages. Sitting on the windshield he signaled his aggression in classic baboon fashion by repeated display of an extreme erection a mere 50 centimeters from our faces. You suddenly find yourself wishing that baboons wore pants.

No problem, I said: Vicki, toss a slice of apple out the window as far as you can, and I will peel off to leave this miscreant behind. Ha! Even with the engine revved, and the clutch popped immediately, the baboon was back on the hood (aka bonnet), apple in mouth, before the car had moved 5 feet.

No problem, I said again. We will drive with our living hood ornament until we enter the territory of the next baboon troupe at that koppie a mile down the road, and they are unlikely to welcome “our” baboon. So, we trundled along, peering past the baboon and his erection, receiving strange looks from passing cars, and as we passed the halfway mark, the baboon got visibly nervous and ceased his destructive efforts. At three quarters, it was over, and in the spirit of courtesy, I stopped to let him jump off and start loping back toward his own koppie.

Another tourist car passed us going in his direction, and as they passed "our" baboon, I peered in the review mirror and saw the red of the brake lights, and I knew that the baboon had his next sucker and ride, and the extortion had begun again.

So, I think you can understand why, walking along that mountain trail, my attention was on the baboons rather than the lovely Protea repens blooming just beneath that outcrop.

As you may know, the UC Botanic Garden in Berkeley has a great Southern Africa hillside, with protea but no baboons. Tons of soil had to be excavated and replaced before the plants could become successful. Each spring it blooms magnificently. This morning I had to chase "invasive" turkeys out of my garden in the Berkeley flats. Not as scary as baboons but quite destructive. Love your stories and illustrations.

Human encounters with the nonhumans’ worlds tend to amaze, terrify, and entertain not simply inform us! Love this one!