In 1998, four years after the end of apartheid, we made the first long visit to South Africa in 16 years. With the end of the violence of the 1980s, South Africa was again relatively peaceful, and we longed to see our friends and to visit some wild animal parks. The country had changed greatly in interesting ways since our times in 1970 and 1982 and I wrote a series of short vignettes about our more memorable experiences. I am posting these as a (previously unnamed) series called African Vignettes. Where appropriate, I have updated their subject matter. Here are links to the African Vignettes posted so far: No. 1. Alternative Wildlife Spotting; No. 2. Wired Folk Art; No. 3. Fynbos; No. 4. Afoot Among the Wild Animals; No. 5. Squatters; No. 6. Working for Water.

From his arm-chair in the living room, Mark held up a finger to stop the conversation. “You hear that? …Shots. …Probably taxis.”

Well, not the taxis, actually. The drivers or the owners of taxis.

The entrepreneurial freedom of the New South Africa has created interesting enterprises, among them a new system of transportation based on privately owned mini-buses that function as jitneys. These are referred to as black taxis, although most of them are white or blue or tan, but their passengers are always black. The roads are full of these taxis, and the taxis are almost invariably full of people, packed in beyond the limits of comfort or safety. They are cheap and they go when and where people need to go, forming a spider web of routes that cover the landscape.

Like wire sculptures, the black taxi system is another example of human inventiveness. None of the taxis have signs indicating their route or destination, so the people waiting on the roadsides have no idea which taxi to flag down to take them where they want to go. There has evolved a totally new sign language through which the potential passenger on the roadside signals to the driver, who is usually barreling along at excessive speed, how far and where he or she wants to go. If this coincides with the driver’s route, and there is room in the taxi (that is, if it contains fewer than 18 adults), the driver will stop. The utility of such a system is obvious, especially in cities with millions of people and many possible routes with hundreds or thousands of taxis crisscrossing them.

For the owner, a taxi is a gold-mine. Even if fares are low, you can pack in 15 to 18 riders, about 2 ¼ tons of human flesh, bone and sweat. Tires belly out and the vehicle hulas from side to side at even moderate speed. But the taxis are always underway, often at high and dangerous speed, and the money keeps rolling in. With so much money at stake, and a new government that has left a regulatory vacuum, the competition for routes, turf and terrain is sometimes pretty raw. Bullets often determine who gets a route. People die in the street. These are The Taxi Wars, and are fought with all manner of weapons--- from simple revolvers to AK-47s. Thanks to the long wars in southern Africa and the struggle against apartheid, guns are easy to come by.

The future of this taxi system will be interesting to watch. Surely the price of competing by shooting it out on city streets must be high, both in human lives and anxiety. I imagine that it is exactly such a situation that leads to calls for government regulation. The government is the third party that keeps us from having to shoot each other. Like the wild west, driving a taxi will eventually become a lot safer but a lot less exciting.

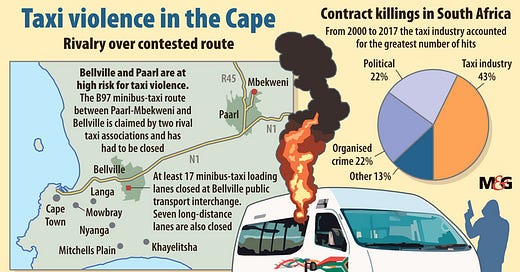

Addendum in 2025: Since our experience in 1998, the Taxi Wars have only gotten worse. Their early phases followed the apartheid government’s decisions to allow blacks to run taxis, mostly 14-seat minibuses. Although it was expected that the violence would subside with the end of apartheid, the opposite happened.

Taxi drivers organized, or were forced into several associations that then competed, often with violence, for routes. The government’s flaccid attempts to regulate taxis mostly failed, and the taxi business became a criminal enterprise, essentially a mafia. Independent drivers were extorted or murdered, and the battles between taxi associations resulted in hundred of murders (about 3000 murders between 1991 and 1999 alone).

More than 80 people died in a single month in 2021, and the war continues with little sign of abating. Taxi drivers have several times torched commuter trains to increase taxi business, with over 140 rail carriages destroyed in a coordinated attack in Cape Town in 2018. Sadly, passengers are often caught in the crossfire, and of course they often take their own lives into their own hands by riding in taxis with reckless drivers. Taxi accidents often result in more than ten and up to 18 deaths. On a few occasions, the government has shut down all taxi traffic for a period. Many people were unable to get to work, causing some to lose their jobs, shutting down hospitals and other essential function. With the advent of Uber as competition, taxi associations threatened and murdered many Uber drivers. As I said above, “such situations …call for government regulation. The government is the third party that keeps us from having to shoot each other.” In South Africa, the government has failed in its duty as the third party and shooting each other has become commonplace.

It almost sounds like the RSA is a failed state!