Dedicated, with affection, to my brother, Henry M. Tschinkel (1938-2021)

Ever since Henry had arrived in Carthage, Tunisia, he had dreamed of a trip into the Sahara Desert, seduced by traveler accounts that there had once been giraffes, crocodiles, elephants, trees and even fish in the middle of what is now the barren Sahara Desert. Because Henry and I shared a taste for travel of a wilder type, he finally got an opportunity for such a trip when I visited him in Tunisia in March 1974. We carefully planned and assembled our gear and food for two weeks in the desert, keeping in mind that we would have to lug all this stuff. As in our Boy Scout days, we pared and winnowed down to what we thought was a manageable amount of “stuff.”

A short flight from Tunis, a change of planes in Algiers. As the propeller plane droned southward from Algiers, the green of the coast rapidly gave way to brown with occasional irrigated patches of green and then to endless shades of brown. Motionless waves of sand lapped at the feet of stony mountains. For the final four hours, no sign of human habitation until the plane touched down on the dirt airstrip of the oasis of Djanet, Algeria, in the center of the Sahara. Closely clumped adobe houses with tiny windows clung to the slopes, while on flat terrain below stretched reed-fenced irrigated garden patches and date palms, defending against the desiccating winds. Ditches distributed the clear water without which this land would be as barren as the surroundings.

Touaregs, one of the Berber peoples, made up the majority of the Djanet population. Touareg society is organized as a caste system, with a warrior class at the top, and a slave class at the bottom. In between are craftsman and merchant castes. For almost two millennia, the Touaregs were a nomadic people, and operated trading caravans carrying gold, slaves and salt from the great cities of the Sahel to the northern edge of the Sahara. Equal parts raiders and guides, when they were not guiding their own caravans across these desiccated expanses, they mercilessly attacked other caravans. When trucks replaced camels in middle of the 20th century, caravaning dwindled, and the fiercely independent Touaregs settled in villages such as Djanet, living off their herds of sheep and goats, and the vegetables and dates produced on their irrigated plots. With the independence of Algeria came the (nominal) abolition of slavery, depriving the Touaregs of a great deal of the labor they had exploited for centuries. Our arrival in their land followed closely on these major shocks to their culture.

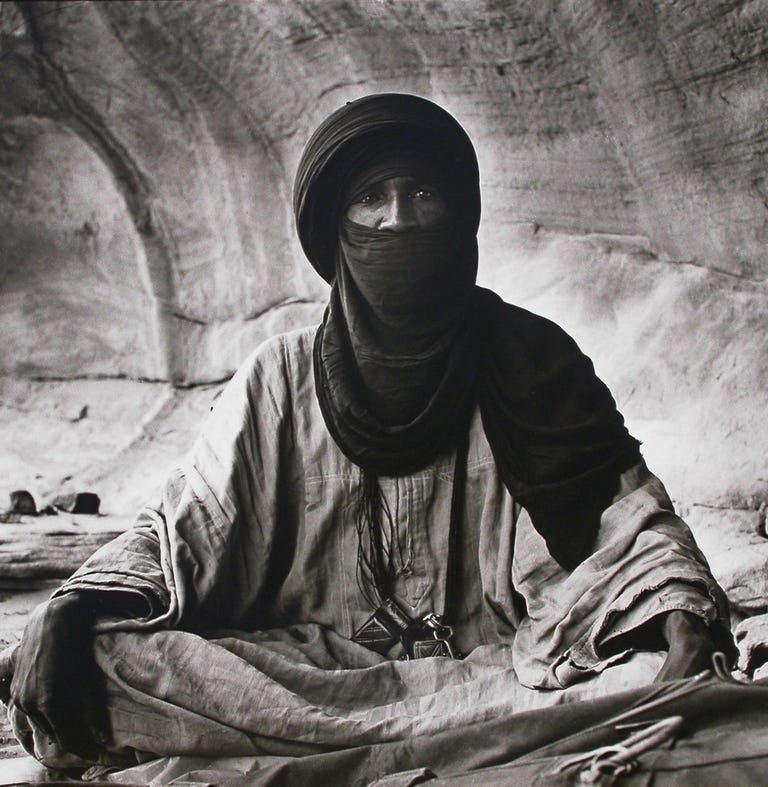

In contrast to the customs in other North African countries, Tuareg men cover their faces so that only their black eyes are visible. On the other hand, in this matrilineal society the women do not cover their faces, demonstrating their status and independence in Touareg society as they flow by with long colorful robes fluttering in the constant wind.

The area we intended to visit had recently been declared a national park, and access for tourists had been greatly restricted to safeguard the neolithic rock paintings we had come to see. Visits were only possible under the guidance of licensed guides and porters. We negotiated for a Touareg guide and a donkey driver to oversee our baggage for the ten days. As they spoke Touareg but no Arabic and only occasional words in French, communication was rudimentary. Both men covered their heads and faces with the traditional, indigo-colored or black turban.

In the cold desert dawn, we shouldered our backpacks, watched as our guides loaded the donkeys, and followed our guide, Ali Ten, up the steep, rocky trail that wound its way up a narrow canyon to the Tassili N'Ajjer plateau 500 meters above. The driver, Barka’s haunting singing echoed and reverberated from the vertical canyon walls. After several hours, we reached the top of the plateau with its fantastic, towering, wind-sculpted sandstone pillars and vertical cliffs that dwarfed our small caravan. Only the squeaking of dry sand under our feet broke the silence. We wove our way over the flat ground between the convoluted brown, red and yellow banded sandstone formations until the evening shadows filled these canyons.

For the last hour before camping, our guides used their loose blue gowns as a pouch to collect any twig that had broken off the occasional bush. We made camp under an overhang, and soon a small fire was making our shadows dance on the wall of the cliff. As desert people whose existence depended on water, our Touaregs only once showed us a pool. Most evenings, one of them simply disappeared and returned with water sometime later. Much of the water seemed to reside in pools under jumbles of huge boulders, protected from the desiccating sun and wind.

As old campers, Henry and I prided ourselves on traveling light, but the Touaregs shamed us. For food they only carried a bag of whole wheat flour, a bag of dried tomatoes and small bags of salt, sugar, tea and yeast for the ten or more days’ trip. Every evening, Barka kneaded dough in a washbasin, and after the fire had burned down to coals, he raked it away, made a small depression in the hot sand, plopped the dough into the depression and covered it up with hot sand, followed by the embers on top. While waiting for the bread to bake, we drank tiny cups of their very strong, sweet tea. An hour later, Barka dug up the baked loaf, brushed off the sand and shared their bread with us. Not a grain of sand adhered to the bread (since then, on sandy beaches, Henry amazed many of his friends with this ageless trick). Under the clear, cold desert sky, we curled up in our sleeping bags with our clothes on, listening to the singing of our companions.

The next morning, we arrived at the first of many overhanging cliffs that were alive with paintings of herds of long-horned cattle in red, brown and ocher, and a confusion of figures shooting with bows and arrows. For five days, we wandered through this Neolithic art gallery. All the surviving paintings were under protected overhangs carved by wind-blown sand. Slot canyons were usually wider at the bottom where the wind had whipped erosive sand through them and worn away the soft sandstone.

Etched into a bare rock ledge, an elephant seemed out of place in these canyons, as did giraffes, antelopes, ostriches, crocodiles and even fish. It is unimaginable that any of these animals could survive in this desert under present conditions. What had happened? The oldest, very primitive petroglyphs, were over 10,000 years old, drawn as the ice cap was retreating across Europe. More recent paintings showed herds of long horned cattle, lovingly rendered in detail and herded by figures with negroid features. Various other activities of the daily lives of these pastoral people were recorded on these sandstone walls. For thousands of years, this area was home to nomadic herders. The most recent paintings were simply triangles with legs, and primitive stick figures of camels. But camels were introduced by Arabs during the Muslim invasion, so these paintings were made after about the year 800. Even chariots with stick figures raced across the walls.

The full sequence of rock paintings records the Saharan climate change during the last 10,000 years. At the time the first painters began decorating these cliffs, these highlands probably resembled the savannas south of the Sahara--- grassy expanses with scattered trees and depressions harboring fish and crocodiles. As the climate warmed and dried during the following centuries, the winds of drought had blown away the topsoil and left desolate sand and rock.

I will let Henry tell the rest of the story---

One day Walter and I climbed one of the taller pinnacles for a view. Because of the many crevices, natural steps and handholds scrambling up was not difficult. From the top we marveled at the endless labyrinth of gorges and towers stretching in all directions. I carefully eased my way down via the same route we had taken up. Looking up, I saw Walter trying a different route above an overhang. “Why is he taking this risk?” I thought. Suddenly, a rock handhold that Walter used broke, and he stepped out into space. The scene of Walter falling 10 meters, his legs moving frantically in the air, will be etched forever in my memory. In panic, I sprinted to the writhing figure on the ground. Miraculously, he had landed on his feet between numerous large, jagged boulders. He moaned from the pain in his feet, ankles and butt. Between the three of us we carried him to a nearby overhang and laid him on our sleeping bags. His ankles swelled grotesquely and turned blue. We could not tell whether he had broken bones. Walter soon became very stiff, and it was painful for him simply to roll over. We improvised camp and I tried to ease his pain with Demerol, a strong painkiller, and even hypnotism once these ran out.

How to evacuate Walter? We naively thought he would be able to walk after a few days of recovery (ha!), but by the second day, we realized that this was not going to happen. The donkeys were not strong enough to carry a man. Because there was no wood of any size, we could not even improvise a stretcher. Stuck in the middle of the Sahara! For three days that seemed to drag on endlessly, our guide, Ali, disappeared for hours trying to find help to transport Walter back to Djanet. All the while, Walter got stiffer and stiffer.

One evening, Barka, our driver, began primping mysteriously, tying his turban in an especially elegant fashion. Walter struggled onto one elbow and took the picture at top of this essay. A young woman appeared in the distance, backlit by the setting sun, and Barka walked out in his carefully coiffed turban, robe, and accoutrements to meet her. The two then vanished for hours. A tryst here in this uninhabited wilderness? I think we outsiders greatly underestimated how many people lived here, and how much they were in communication, but with few words in common we could not clear up this mystery.

Our food was running short, and Walter’s condition was not improving. His pain continued. How much longer? Finally, in the early morning of the third day, I exclaimed, “Hey, Walter, is that a mirage or a white camel in the distance?” White camels are rare but seemed like an appropriate color for an ambulance. However, it was impossible for Walter to sit, much less to sit on the camel. The owner of the camel said, “During the Algerian war, we used to evacuate the wounded by tying them around the hump of the camel.” In that painful position, with legs dangling sideways, we set off for the edge of the plateau half a day away. There, to our dismay, we learned that camels are not able to walk down steep, rocky trails. From that point we had no choice but to have Walter sling one arm around the shoulders of Ali and the other around mine and slowly to hobble our way down. We interrupted the excruciatingly slow pace with frequent stops to let him rest his agonizing feet. His exhaustion and the dimming light forced us to camp halfway down from the plateau in a sandy spot under sheer canyon walls. The next morning, we resumed our torturous way. The narrow canyon heated up as the sun rose higher. At last, shortly after noon we reached the trailhead and hitched a ride with a Land Rover that had just dropped off another party.

Our hope for finding medical assistance in Djanet was quickly dashed. The young, bored French intern in the miserable, bare dispensary helped to gingerly balance Walter on a tall stool so that his feet might reach the height of a fluoroscope machine designed for chest X-rays. He concluded, “Je regrete, but the resolution if this machine does not allow me to determine whether a bone is broken.” Consequently, the intern could do little more than administer pain killers. At least Walter now lay on a bed in the dispensary instead of on hard sand.

Our return to Djanet coincided with a Touareg festival, complete with dancers, camel parades, robed but barefaced women, robed men with turbans and covered faces, children, and a lot of dusty commotion. Walter borrowed crutches from the dispensary, and we hobbled into town to watch the festivities.

I set off to arrange our trip back, something made more difficult by our not being able to exchange our traveler’s checks. We had been short of money during our whole trip. For three days, I made numerous desperate visits to the airline office to ask the unfriendly, even hostile Algerian authorities to change our tickets. “We cannot promise you space. Come back this afternoon.” Wait, patience. “No, the plane could not land yesterday because of the sandstorm. Come back tomorrow.” On the third day, they grudgingly handed me the changed tickets. After more hours near the runway, finally, a droning silver speck appeared in the sky. The Viscount Turboprop circled and raced down the runway in a cloud of dust. At the top of the steps to enter the aircraft, Walter delivered his borrowed crutches. We slumped into our seats with relief, erroneously thinking that we were almost home.

But no, back in Algiers, no connecting flight and no hotels were available that day. We had no choice but to hobble out to a dew-wet field in front of the international airport and to throw our sleeping bags onto the ground to await the next day. We shivered through the clammy night.

In Tunis, the doctor determined that Walter had no broken bones, listened to the story of the fall, shook his head slowly and said, “You Americans sure are tough.” But not tough enough to qualify as a cowboy movie where the hero gets up and, perhaps limping slightly, walks off into the sunset. Walter walked on crutches for about six months and felt the aftermath of this accident for over a year. To add to his misery, he missed the Pan-Am flight from Paris to New York because of traffic jams on the Paris ring road. He knew he would be in trouble with his wife, who did not yet know of the accident, so he had grown an anemic mustache while recuperating, hoping it would distract her from the fact that he was bent over slightly and walked with a cane. The ploy worked for about one third of a second. He had to pay for his non-communication for years to come, for his wife didn’t trust that he would behave differently if there were a next time. To some degree, she tried to discourage him from taking more risky trips with me, something he more or less ignored.

For me, the experience reinforced the lesson that had shaken me before on a fold-boat trip down a tributary of the Orinoco River. We protect ourselves against the risks we foresee, but in our civilized lives and especially in the wilderness, the undramatic loose rock, the pathogens in a drop of water, the wrong turn can end in disaster. For the hunters, herders and warriors who produced those wall paintings full of action and danger there must have been many an accident caused by a minor error. Even the Touaregs of Djanet and others living in remote places do not have an easy way out after a mishap. The “simple life” in out-of-the-way places might seem appealing – as long as we have access to X-ray machines and a quick escape in case of trouble.

I’m sorry for the loss of your brother. You both must have been nurtured by someone who shared a love of adventure and storytelling with you.

I always enjoy your newsletter. Thank you, Walter.