Creatures that are very long-lived don't have to reproduce successfully very often to stay in the game. Theorists call this hedging bets, and indeed, bet hedging is a favorite explanation for why plants and animals mostly don't reproduce only once in their lives. The argument goes that even if they could produce only one (yes, one!) more offspring by expending all their effort in a single reproductive event rather than reserving some resources for the next event, they would have replaced themselves and be ahead in total offspring left behind. But this brainy theory is a pipe dream, for it fails to account for the fact that in many environments reproductive events are not all the same, and complete failures may follow one another for years. As a result, most creatures do not put all their offspring in one basket, choosing instead to live longer and try more often.

When reproductive success is rare, as it often is in harsh, variable, or extremely competitive habitats, this extension of life may be extreme. Among the most extreme are the bristlecone pines found as isolated populations at high altitudes of several mountain ranges in the western USA. Life here is arid and very cold, the soils are too stony and alkaline for most plants, the elevations (up to 11,200 feet) are above the normal treeline, and the windy winter weather is challenging to lethal. No wonder then that some of these hardy, extremely slow-growing trees are the oldest known individuals on earth, often living more than 4000 years (the oldest is 4,855 years old). As difficult as it may be to comprehend, in a stable population, a tree is likely to produce only a single surviving offspring during its lifetime.

Because bristlecone pines can be so old, past climates can be reconstructed from their growth rings and the composition of their wood. High elevations and short growing seasons assure that general climatic trends are sensitively recorded in the width of growth rings, and that stable carbon isotope ratios in the wood distinguish wetter and drier years. Counting the rings backwards results in exact ages, and because the formation of new carbon-14 in the atmosphere is not constant, the carbon-14 levels of this exactly-aged wood can be used to correct the carbon-14 dating scale, with great importance to archeology and ecology. Because dead trees do not rot in this environment, cross-dating the rings of living trees with wood debris has created a 9,000 year record.

It often isn't too hard to tell how successful a plant’s life strategy has been --- the frequency of young and half-grown individuals tells the story. When all the trees are ancient, and young trees are completely absent, you can be sure that these ancients have not successfully reproduced in a very long time. My brother and I once saw ancient cypress trees in the Sahara Desert without a single tree less than a thousand years old within hundreds of miles. These wizened ancients had hedged their bets and lost them all as the Saharan climate dried, but they were still trying. Unless the climate changes a lot, they are the last of the Mohicans.

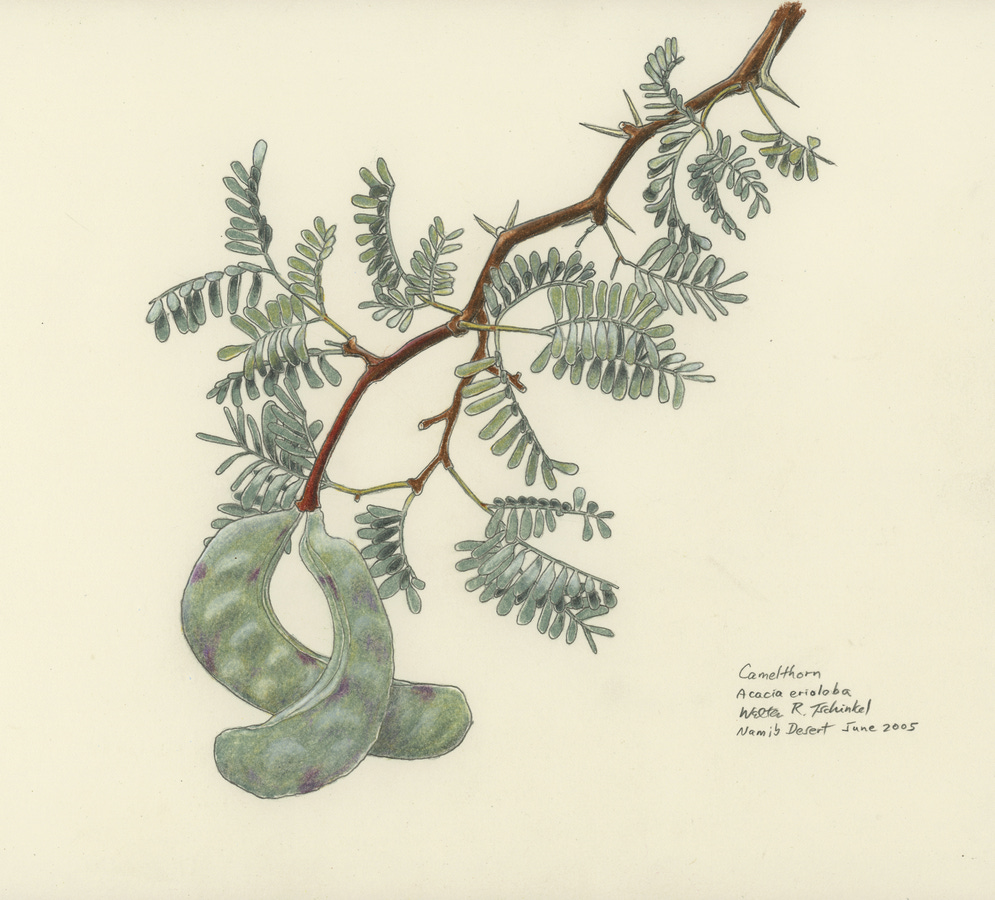

Something similar may be happening in the camel thorn forest in the deep red dunes at Wolwedans in the Namib Desert. "Forest" seems a bit of exaggeration, for the trees are often hundreds of meters apart. But then, there is probably a fuzzy line between forest and a non-forest collection of trees anyway. The fact is that there are no descendants of these venerable acacias, even though abundant seed pods adorn the trees (as in my drawing above). The inevitable death of old trees simply thins the trees even more, a process that seems to have been going on a long time. So, unless these acacias have some better years, they will be like the cypress trees in the Sahara.

In fact, looking back, the entire Erioloba "forest" could have been the outcome of a single good year or two, conditions that have never recurred since that golden time. Many bad years can follow one or two good years. Seen more broadly, humans are also subject to the same inevitability. Greenland was colonized by the Vikings during a brief period that was favorable to dairying and farming, followed by repeated failure of reproduction of both Vikings and their animals (and eventually of the survival of both) that erased European presence on the island for centuries. Perhaps the Erioloba forest of Wolwedans is the Greenland of its species. We should have the answer in a few centuries. But if all of humanity is also the outcome of a brief golden time, there may be no one around to listen to the tale.

Your last line puts life in perspective.

A very informative, soberingly precautionary account. Restacking to Notes.