In 1979, I was doing a research project that had me crawling around in piles of bat guano in the hot attic of one of the buildings of the Pan American Agricultural School in El Zamorano, Honduras. I wore a respirator to keep from getting toxoplasmosis and had been vaccinated against the rabies carried by the vampire bats that roosted together with the three other bat species. But this essay is not about a pile of guano, but about a chance observation I made on the drive from Tegucigalpa where my brother lived to the School in El Zamorano where I would marinate in bat guano for several days.

On the way, my brother and I stopped at a typical, low-budget roadside joint to have a refreshing drink, it being hot and humid. The walls were simple pine planks nailed to studs. No any inner walls of fancy Sheetrock here. The pine was from old, mature trees from the virgin forests in the highlands . As we sipped our Nehi sodas, I faced the wall whose outside was bathed in brilliant sunlight, and in the dimness inside, the wood glowed with the color of honey as though illuminated from within. Large streaks, knots and blotches of the planks were so saturated with pine resin that they became translucent, passing sunlight through ¾ inch of wood to create the glow I was enjoying over a Nehi soda.

In my mind, and probably most people’s, wood had always been an opaque material, blocking the passage of light, making the insides of boxes and houses dark. But here was wood, and rather thick wood at that, allowing the passage of light, and revealing real beauty in the bargain. This new understanding gestated quietly in my brain for forty years, in dormancy like the durable eggs of brine shrimp in a dry lake. But like rain filling a dry lake, unnoticed and unconsciously, step by step, the conditions for a reawakening of that understanding began to accumulate.

The first condition was that my wood-scrounging-self realized that lumber here in Tallahassee could be had for free or almost free if one visited old buildings that were being demolished to make way for new ones. If they dated before about 1920, their structure was made of “heart pine”, wood from mature pine trees that had once made up the southern longleaf pine forest. For the uninitiated, there is little resemblance between modern, second-growth pine and this ancient heart pine--- wide vs. tight growth rings; mushy vs. hard wood; pale boring color vs. honey to dark to red color; little odor vs. heady turpentine smell. The list goes on.

Ignoring conventional wisdom that pine was a wood suitable only for 2 by 4s for building tract houses, I started building furniture of this heart pine, enjoying the feel, the beauty, and the smell. This was not wood to be wasted on floor joists, rafters, wall studs and other invisible structures, although that is exactly where my salvage came from. Perhaps it takes the insipidness of modern, second-growth pine to make one realize the beauty of this hidden old stuff.

Some of this heart pine was so resinous, and the sawdust so sticky that it formed stalactites and stalagmites on and under my table saw, deposits that upon standing a few minutes sometimes solidified, freezing the saw blade when I hit the “ON” switch again. The turpentine odor that permeated my shop and the quirky pleasure of this phenomenon were fringe benefits of working with this pine.

The next condition came into focus gradually--- when occasionally I sawed the resinous wood into thin slices and held them up to the light, a lovely honey glow tickled a vague memory implanted somewhere in the recesses of my brain. Something suggested that I had seen this movie before. I don’t know why it took so long to connect that glowing Honduran wall with the honeyed light passing through slices of heart pine, and to realize that I could do something very un-wood-like with this heart pine wood, namely, I could use it like stained glass to create luminous furniture. The light would be provided by my other obsession, LED lights in various forms.

Sawing the wood thin of course reduced its stiffness, so in my first illuminated piece, a small side table, I glued the strips onto plate glass cut to fit the frames. The resinous wood came from a piece of floor joist with a prominent knot/branch, something that would not have been suitable for “ordinary” furniture. Making the sides tilted from the vertical changed it from a simple box to something a bit more interesting, and a simple LED bulb inside made it into a piece that demanded notice. I mean, how many times do you see tables that glow, right?

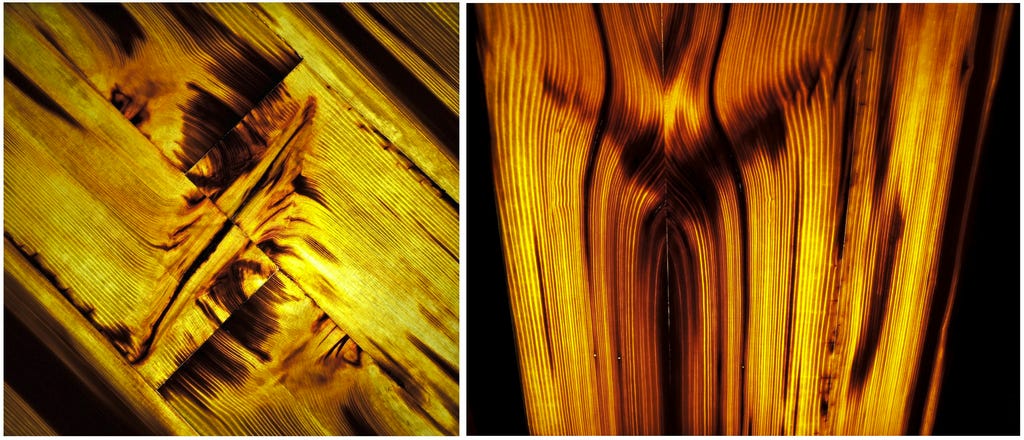

Here is some of the wood in greater detail, showing the beauty of the patterns.

From this point on, it seemed inevitable that I would build a piece whose whole point was the translucent beauty of the wood, and whose practical use was marginal, at best. A yard light seemed a good choice. In another one of those intersections that justifies scrounging, the glass for this project was left over from a field research project from 20 years previous whose purpose had been to collect flying insects, especially newly mated queen ants. These so-called window traps consisted of a big pane of clear glass with a tray of alcohol or soapy water underneath. Flying insects that bang into the window drop into the alcohol to be preserved for later collection and counting. To keep the fluid from evaporating too fast, I had several hundred narrow strips of glass cut to fit the trays. After the project ended, these glass strips were stacked on my lab table for many years, because I couldn’t bring myself to throw them out. Because… well…you never know….

You truly never know…I cut the glass strips at the correct angles to fit into the eight-foot-tall frame with narrow cherry strips separating the glass. An angle guide helped me cut the glass at the correct angle and to the right length for its location in the frame. Thin strips of heart pine were then glued onto each piece of glass and installed in the frame starting at the bottom, synchronized on all four sides. Keeping the lightweight frame from bowing out as the strips were added was tricky.

A PVC pipe with LED strip lights on four sides was mounted in the central axis of the frame. Aluminum angle irons in the bottom were ready to mount to a cement base behind the fishpond in our yard. Here is the complete light, still in my shop, with details of the sides.

Once mounted, we programmed the light to go on at dusk every night, and this greatly pleased our gorilla. The following year, I built another much smaller and simpler yard light that I mounted farther back in the bushes, and this pleased our gorilla even more.

Could I build illuminated furniture without glass? Not if the whole thing was made of thin slices, but what if only some parts were? My chance came when Erika asked me for a cabinet for her electronic equipment, what back in the Electro-Pleistocene we called a “stereo cabinet.”

Again, heart pine was the choice of wood. I decided to go for “accent” rather than “grand.” In each of the cabinet doors, I routed three elongated slots all the way through the wood, with a narrow outside shoulder to receive an inlaid piece of thin, translucent heart pine. On the inside of these slots, I installed strips of 100-mesh stainless steel screen to which were attached strips of 12v LED lights. I used screens to avoid overheating the LEDs in closed spaces and wired them to a dimmer so the light level could be set to taste. To avoid flexing the wires as the door was opened and closed, I left a small gap in the piano hinge and wired one part of the hinge to the positive and one to the negative poles. That way the current got from the power source in the box to the lights in the doors.

Other than the fancy illuminated doors, the cabinet was just a rectilinear box of very pretty wood with shelves for the equipment. As I wrote in an earlier post, anyone with a tape measure and a carpenter’s square can build that. We shipped it to Chicago by UPS, and it arrived without a scratch. So here it is in Erika’s apartment, illuminated and not illuminated.

With the lights on, it hearkened back to that roadside joint in Honduras. It took several decades for those glowing pine plank walls to come together with particular materials and ideas to produce these three illuminated pieces. I suppose I could regard these as a sort of “proof of concept”? If so, what’s next? For the time being, this question is gestating in my brain. Somewhere in the back of that brain is an idea waiting to be born. Let’s hope it doesn’t have to endure another forty-year gestation.

Ever creative, your writing glows. I’ve forwarded it on to a young friend, a furniture designer and builder, who will appreciate your passion for wood.

What light through yonder pine board breaks? Thank you for sharing memories as beautifully written as creations you have crafted.